A Day in the Life, Houseless in The Dalles

Pictured: A tent pitched on the sidewalk in downtown The Dalles. Urban camping by houseless individuals is more common in communities that do not have year round Pallet Shelter of SquareOne Village programs.

A quick note on language: Instead of using outdated language like “homeless” to refer to those experiencing houselessness this article uses the term “houseless.” Why? Well, it is both a more correct and less stigmatized term. While the people interviewed in this article may not have houses, that does not necessarily mean they do not have homes. Some still consider The Dalles their home, even if they cannot afford a house here. A home, after all, can be wherever you lay your hat or have a smiling face waiting for you. Learn more here.

A note on perspective: Some of what you will read will be about me confronting my privilege as a person who has never experienced what it’s like to be houseless until now. But this was my experience. It is specific to me and subjective to the moment. Some of what you will read might make you smile and some of it- well if it doesn’t bring you to tears it might at least make you feel angry. How it makes you feel, will be your experience, not mine. I encourage you to go out into the world and experience what it’s like to know The Dalles's houseless community for yourself.

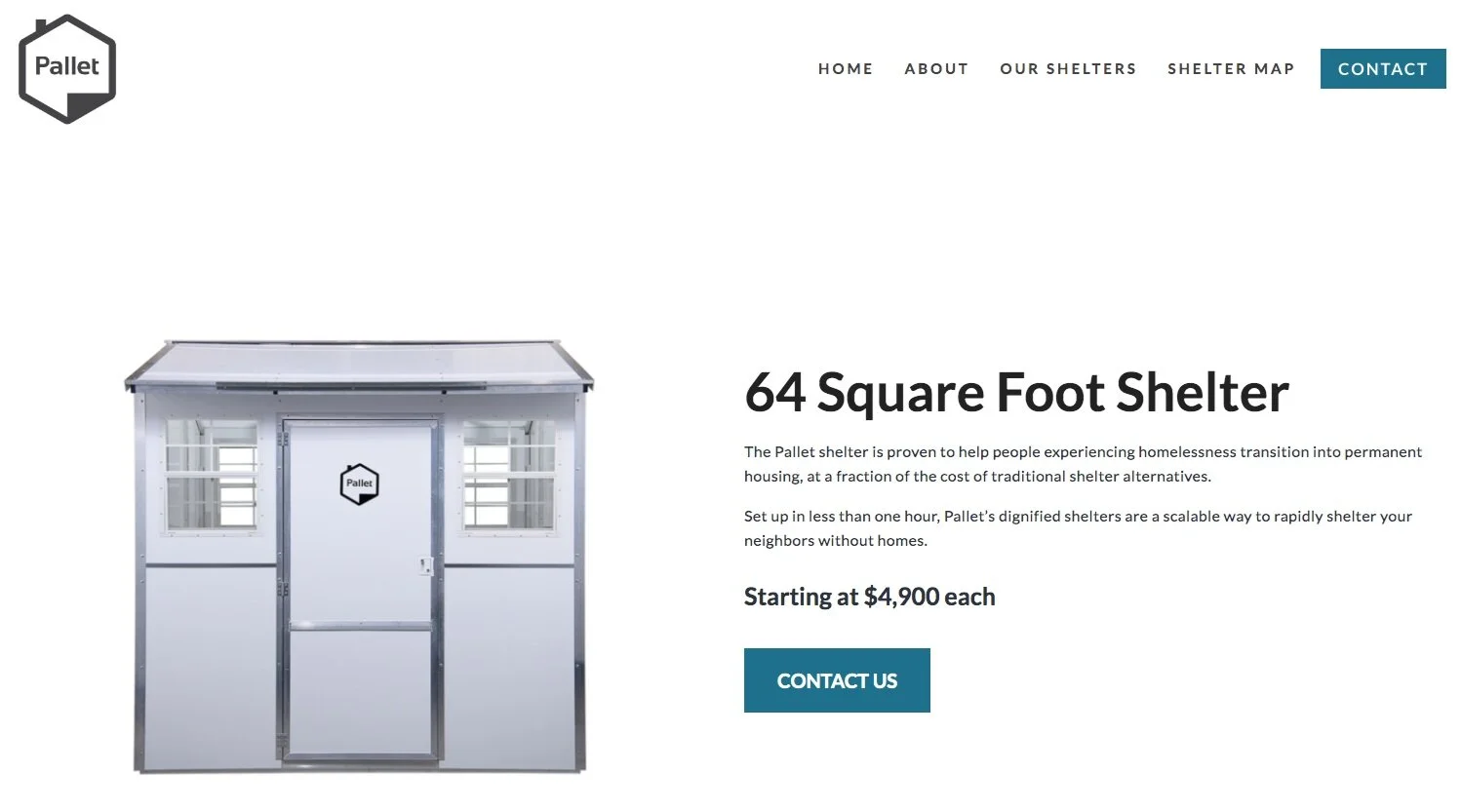

My name is Cole Goodwin, and I’m a journalist for CCC News. I’m also a business owner and long-time resident of the Columbia River Gorge. The Dalles is my community, and I’ve made it my job to learn about it and try to make it a better place in any way I can. So, when I found out that Darcy Long Curtis had received a $45,000 grant through the Mid-Columbia Community Action Council to build temporary pallet shelters for those experiencing houselessness in our community, I asked Darcy if I could stay in one and write a story about what it’s like.

What I learned has changed me forever.

It all started with a text

Darcy Long Curtis messaged me on January 20th at 5:22 AM, “The shelters are up, and I have one you can sleep in.”

The day had come for my stay in the pallet shelters.

Source. 15% of people in the Mid-Columbia area live at or below the federal poverty level.

I decided not to overthink it too much. Houselessness rarely happens on an individual's preferred schedule. Those who become houseless rarely have time to plan when sh*t hits the fan, so to speak. Rarely would someone get connected to alternate housing as fast as I was about to. Usually, someone would have to go through a process of filling out paperwork to get into one of the Pallet Shelters. I had skipped this process, however, due to the good fortune of having a press badge. My privilege would follow me even as I tried to live a day in the life of a houseless person in TD. I packed. I kept it simple. I threw a sleeping bag, water bottle, two extra pairs of socks, and a cliff bar into my backpack and called it good. I decided I’d take meal breaks from the experience - I wasn’t going to eat donated food that wasn’t meant for me, and I’d need the time to jot down notes as I went along.

Pictured: Pallet Home Houseless shelter and volunteer trailer on Bargeway Road in The Dalles.

I arrived at the pallet shelters around 3:30 p.m. on Wednesday afternoon. My first impression was of a gravel lot on which 18 carefully numbered, identical, symmetrical, utilitarian, white, and sterile looking tiny houses had been uniformly spaced and placed in neat rows like so many shiny teeth. On either side of the lot the noise of industry, semi-trucks and forklifts could be heard echoing across the landscape of the small utilitarian urban survivalist village for those with nowhere else to go. There is no shrubbery here, no greenery to lessen the sharp edges, just a gravel walkway, and a gravel drive and a line of three porta-potties stationed a merciful distance from the shelters. The concrete barriers surrounding the gravel lot also didn’t give the place a very inviting aura. But besides the activity at Northwest Natural Gas all was quiet. Nobody seemed to be around. So, I went to check-in at the volunteer trailer to find out which tiny house I'd be staying in for the night.

I knocked. Darcy opened the door to the trailer.

“Let me put my shoes on," she said.

With the door of the trailer swung wide I could see donated items everywhere- clothes, DVD’s from the library, books, other bags full of stuff I couldn’t identify. Residents of the Pallet Shelters check out the DVD’s and books and can watch them using a portable DVD player that gets handed around. I could see how these items would enrich the residents' experience, but it sure looked cramped in there for the volunteers.

Darcy told me I was going to be sleeping in Pallet Shelter number four, one of the originally built shelters. I thought the number to myself in my head. Trying to be sure I remembered it. Quatro en Espanol. Shi, in Japanese. I recited the Harry Potter series' iconic opening line to myself.

“Mr and Mrs Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. They were the last people you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious because they just didn’t hold with such nonsense…”

I wondered if I was walking into some nonsense that the Dursley’s would disapprove of. Probably. Good, I thought.

Inside the shelter, no bigger than a small bedroom, it was just about as stark, white and cold inside as the outside. Two fold-down beds were attached to the wall on either side of the room and two mattresses lay on the ground wrapped tightly in white plastic. Morbidly, I thought that it looked like it could be hosed down clean of any manner of mess with ease in only a few minutes if need be. I imagined the worst. I shivered. Darcy turned on the heater located on the wall in between the two beds.

Pictured: Pallet Shelter safety information is clearly labeled in bold san serif font.

In the center of the wall between the two beds were several outlets for electronics, a set of shelves, windows, an electrical breaker box, and a wall heater. No kitchen but Darcy tells me that some people have a microwave or have a crockpot in their shelters.

There are also no restrooms, hence the porta-potties.

Pallet Homes website lists three reasons they designed their shelters without restrooms which I’ve abbreviated below. Click here to read the full post.

Reason #1: Shelters without restrooms are faster, easier, and more cost-effective for cities and human service agencies to build.

Reason #2: Improved outcomes for shelter residents. “Building our shelters without bathrooms is a subtle way to encourage community building among residents. When shelter residents need to use the restroom, they need to walk to the communal facility, interacting with their neighbors on the way.”

Reason #3: A shelter with a communal bathroom is more humane than a tent without any bathroom.

Pictured: Darcy Long Curtis frees a new mattress from it’s shrinkwrap.

Darcy pulled a knife from her pocket and helped me free my mattress from the shrinkwrap. The blue twin-sized mattress popped free. I tested it out briefly and was pleasantly surprised with how comfortable it was. Darcy told me, however, that not everyone likes to sleep on them.

“Some people have opted to just fold it up and not use the mattress at all because they’re used to sleeping on the ground. Others fold the beds up during the day and put a chair in here so they can hang out… because it is a pretty small space,” Darcy told me.

“I stayed in one the first night that we had the first set and before we had any electricity, and that was kind of interesting, but it did give me a different perspective about what it’s like to live in one of these,” she said. “It’s a much nicer place to sleep than what they have, but people shouldn’t think that they’re so cushy that people aren’t going to want to move out into an apartment or something because that’s totally not the case. It’s good for survival but it’s still small and still drafty and all those things.”

Before Darcy leaves me she hands me my key. “So you can lock up your belongings.”

Pictured: Darcy Long Curtis hands me the key to my Pallet Shelter.

I learn that having a safe place to store and lock up your belongings is a big deal for houseless people. Think about it. Without a place to store your stuff, you’d be forced to either carry it with you everywhere you go (not very practical if you have a job) or leave your stuff out in the open and risk theft and/or having your stuff reported as ‘dumped’ and taken away by police. This is a huge problem when it comes to keeping track of things like your driver's license, birth certificate, mail, checks, or your basic survival gear such as a warm sleeping bag.

“A lot of times people steal their identities, drivers license or ID,” Darcy told me “We’ve got a couple of people that are actually working now that they have a place to store their stuff and they are feeling motivated.”

Pictured: Shopping carts on W 4th. (These specific hopping carts are actually used by an individual who is not houseless.) Shopping carts are useful tools for many houseless people who don’t have a place to safely store their belongings and have to carry all their stuff with them. Shopping carts can be used to move belongings over long distances with minimal energy exertion, which is important when you don’t know where your next meal might come from. They can also be covered with a tarp or rain fly to keep out the rain in the wetter months.

Another obvious benefit to a locking door is that it keeps you safe from intruders. But it also offers those experiencing houselessness something even more invaluable: a bit of privacy, which is hard to come by when you live your whole life in the open on the streets.

While Darcy and I stand half in, half out of the number 4 Pallet Shelter, several houseless individuals staying in the pallet shelters walk by. Some avert their eyes, some look directly at us looking openly curious. Regardless, Darcy greets everyone by name.

She introduces me to a houseless individual named, Keith Bright, age 28. He’s just a year younger than me, and I wonder what it would be like if our places were reversed. That’s really what I came to find out, I realized then. Not what it’s like to spend one night in a Pallet Shelter, but what it’s like to live like this every day. I ask him if I can interview him while I’m here. He agrees but is hesitant. He says tonight will be his first time staying in the Pallet Shelters just like me. He looks a bit tired and looks away quickly when I meet his eyes. So it takes me a minute to place him. He doesn’t recognize me, yet, I think, but we used to work together at RiverTap in The Dalles.

We sit down together on the rocky ground and I put a recorder between us so we can chat.

Interview with Keith Bright

Pictured: Keith Bright, 28 stands in front of a Pallet Shelter on Bargeway Rd.

What’s your employment history?

I was working Clocktower and a little bit and before that RiverTap and you know, COVID kinda shut those down. I’d go back to work in a heartbeat if I could.

What was your favorite thing about working in the kitchen?

The people atmosphere, the energy, it was just a good gig, time flies, just a good gig.

What’s your educational history?

Just high school. I was homeschooled here in The Dalles. I graduated.

Is this your first time experiencing houselessness?

Yeah, I mean there was another time very briefly before and then I went into sober living, and anyway one thing lead to another, it was all my fault you know, I just figured one more beer wouldn’t hurt right, and it just takes one. That was a couple months ago. Now it’s like the furthest thing from my mind. I’m just focusing on not dying and staying warm. It’s been about a year, a little under, so it’s not really that bad for the most part. Just trying to stay positive. I always tell myself it could always be worse.

I never thought I’d be in this position ever. No one really does. I went from fast food to Dairy Queen to getting a nice job with good people and everyone seemed to get along really well, and I was, like, ‘awesome, this is great,’ and then about two weeks into it they laid me off because of covid. You know kind of a punch in the gut, but hopefully, reopening isn’t too far off, and maybe I can clean up a little bit and go talk to them over there, and hopefully, they can find something for me. If not, I hope I can find something else.

Do you feel safe here?

Yeah, actually. I do for the most part. When I’m walking around at night I don’t feel like I’m going to get mugged if that’s what you mean. I would go canning (collecting aluminum cans for the deposit money) at midnight, back when you could do that before COVID, and then go back and go to sleep. The Dalles is a pretty quiet town after 10 O’clock.

How much sleep do you get every night?

Well, depends on the weather. When the sun comes up I come up, when the sun goes down I seek shelter. When it’s warm it’s a full night. When it’s been really really bad without any blankets or a camp or anything, you get none. So a couple hours? 2-4? Sometimes you tough it out through the night and when the sun comes up you warm up and can fall asleep. You know really, it’s about what you're comfortable with. I’ve kind of adapted to the cold, but it’s been a challenge.

On average how many meals do you get a day?

I usually get at least one meal, you know. To be honest, if it wasn’t for Community Meals I’d probably be doing a lot worse right now. I’d be in a much rougher spot if it wasn’t for them. Thanks to them I never feel like I’m starving, which is really great. It never ceases to amaze me how nice people are here. I definitely couldn’t be doing it on my own. Food stamps only go so far even with your max benefit, especially when you don’t have a stove or a microwave. And most people can identify if you’re homeless, and people will stop by and share whatever they can spare.

What does the word home mean to you?

A place where it’s warm, someone’s sitting in front of the TV, go home and eat dinner and everyone’s sitting at a table together. And you know-like traditional, like, think Thanksgiving but like less extravagant. You got your family, and you sit down and talk about what happened that day, you know, what happened at school, what happened at work, watch movies, eat popcorn and maybe have some dessert. Just home. A warm place to be with your family. A place that feels safe and secure and there are lights on. Actually, you know, like screw TV at this point, I mean that’s like the furthest thing from my mind. Maybe a fireplace, a dog, just a place that’s homey. Neighbors are nice, and you go out and get the paper and say hi to each other. Just a tight-knit group of people that you live with, and when you sleep you don’t worry about the stuff in your pockets or whatever. Just a safe place with everyone you love around you.

Where do you want to be in a year?

Well, I heard Clocktower is going to be opening up on February 21st, and I would like to go back to work in cooking. I don’t have anything on paper, but I’ve been trained by an actual chef. Roof over my head or not. There’s resources where I can take a shower and clothes and stuff, so, I’d like to get cleaned up and go back to working in the kitchen.

What would help people better understand the houseless experience?

Live a day in the life. That would be the first piece of advice. If that doesn’t work for you, try a week and then you’ll probably get it. I was raised to NOT be like this. My dad lived in a camper and stuff and moved around but never asked for a handout or anything like that, and I had that same mentality growing up.

I was holding a sign pretty recently. You know just “Anything Helps.” I was having a really bad week, and my parents drove by and saw me doing it. And that’s what it’s like out here, you know. Sure people might drive by and maybe shake their head at you, you know. It’s not like I’m buying cigarettes and booze. I’m trying to survive.

Word travels quick that you’re homeless. Most of us are surprisingly, not what you’d expect, if you would actually stop and talk to someone who is on the street. So don’t just be old-fashioned and be well like “Well I worked for everything I have” because most of us did too, and we still ended up out here. Like I said, I can’t speak for everyone. But we’re not all druggies and alcoholics that spend all our money on cigarettes.

How would you like to see people experiencing houselessness to be treated in the future?

Well, this is really good start.

He gestures to the Pallet Shelters.

I’ve never seen anything like this or heard about anything about this, so I guess I was born in the right time for people to actually, you know, take notice, at least around here. This is a really good start. If there’s more community stuff like this or community projects like these tiny homes where people can earn their keep that would be cool. As far as things go, this is a really positive step in the right direction as far as I’m concerned. They’re doing a damn good job. If it weren’t for this and Kerry Ann and everyone at the shelter, I don’t know where I’d be right now.

What’ the worst thing that happened to you this week?

A few days ago it was really cold and I was just trying to stay up and stay warm. But it’s hard when you’re no boy scout you know? I certainly was not a boy scout. My parents took pretty good care of me and I never really had to worry about trying to stay warm on my own. It’s hard to get wet wood to burn so there’s blankets and stuff but when everything is covered in frost and like yeah, that's pretty rough. You just stay up all night either walking around not even really doing anything just trying to keep your body moving and stay warm. And when the sun comes up you’re like ‘Thank God!’ you know, and can finally get some sleep.

What is the best thing that happened to you this week?

He laughs. Wow, that’s a tough one. He laughs again. Wow. That caught me off guard. Uh probably getting in here. Probably getting a chance to be a part of what they’re doing in here because you know over at the Community Meals, there’s almost no one there anymore because of COVID, and everyone is here now, so you go over there, and it’s a ghost town. So it’s cool to be here and have everyone in one place. This has been a really great opportunity.

Oh yeah, and I was sitting in front of Grocery Outlet and someone bought me groceries, that was pretty cool. You know I didn't have a sign or anything. They just came by and asked if I was homeless and I was like yeah, how can you tell?

He laughs again and gestures to his appearance. Right?

I didn't think anything of it. I'm sitting there talking with some friends, and she comes back out, brings out this big grocery bag, with her daughter, and they gave it to me.

And she was obviously teaching her daughter, to you know, not just walk by. I think that everyone should invest those morals in their kid. Not quite like my parents did with that old-fashioned approach you know, where they don't really get it…

He gets quiet and looks a little sad for a minute but continues.

But they don’t hold it against me for being homeless or anything you know. I’m their kid, and they’re still gonna love me. But yeah anyway the groceries were really cool.

He ends our interview with, ”Everyone keep your heads up. We’re gonna be alright.”

Pictured: Keith Bright, 28 stands in front the the Pallet Homes Houseless Shelter in The Dalles

I ask Keith if I can grab a photo and he hesitantly agrees to pose for one. I give him a $10 gift card from CCCNews in exchange for sharing his story with me. Then I thank Kieth and say goodnight.

Darcy is standing in one of the walkways between the houses. She’s holding armfuls of plastic from another mattress she’s unpacked for a new resident. I ask her what she’s doing, and she talks to me about the garbage situation.

“We generate a lot of garbage. Because of COVID everything is paper plates, plastic spoons, plastic forks, whatever. So we can easily fill up a dumpster in a week. When they put the new units in it created a lot of extra garbage,” she said.

“People here keep things very clean. But one thing about homelessness, you do generate a lot of garbage because everything has to be single use. But the single-use was part of the problem happening over at St. Vincent de Paul. People have to take their food to go and they’d sit down to eat somewhere, and there wouldn’t be a garbage can anywhere in sight. Just like anyone you know, some people don’t feel strongly enough to carry it half a mile to throw it away. Some do. Some are extremely clean. With some, I would say it’s an attitude. Some people have been mistreated or people have looked down on them or were just mean to them, and so, they feel like they don’t need to do anything for anybody else, like throw trash away in a garbage can.” Darcy told me, implying the obvious: “If you feel like nothing is ever going to change and people treat you like dog poo on their shoe, it changes you and your behavior.”

I realize then that in addition to that-buying trash bags that you’re literally just going to throw away is pretty low priority when you’re counting every penny to survive. And there currently aren’t very many public trash cans in the downtown to meet the need. I wonder to myself if there is a way to develop a free garbage disposal system for houseless people to use once the pallet shelters come down in March and they no longer have access to the dumpster. I file that thought away for later.

I ask Darcy if it’s rude to knock on people’s doors, and she tells me some people might be sleeping but that’s all. We go knock on Diane and Harold’s door. Harold is sleeping, but she introduces me to Diane who is one of first people to move into the tiny shelters. She tells me she’s lived on the streets for 3 years. She’s short, unassuming and talks with energy.

It’s getting dark and cold out now, so Diane and I go back to my shelter.

Source. Graph showing the average income of people living in the Mid-Columbia area.

Inside my unit with the heater running, I struggle to hear Diane through her mask and the recorder only picks up parts of it. Leaving a bit of disjointed narrative for me to piece together later. Before we’ve quite started Diane gets dizzy, and we have to stop so she can catch her breath. She told me she’s not sure what causes it but thinks it could be diabetes and blames the gas station egg salad sandwich she ate earlier.

Source. Graph showing the average home price working families in the Mid-Columbia can afford.

Diane learned to read using the bible, and she used to work at Oregon Cherry Growers not that long ago. But when her brother died several years ago, she couldn’t pay the house bills with the amount in her disability check. She ended up living on the street. She said she is grateful to be in the Pallet Homes.

“Kerry Ann told me about this place. These places are great. Each one of these units cost $5000. I like it. I got plugins; I got a crockpot, microwave; I’ve got a steamer so I can make things soft, so I can eat it. I’ve already got a job here cleaning up. Well maybe, a lot of people don’t want us here. Not sure where we’re going to go after this.”

Do you feel safe here?

Yes, I do.

What does the word home mean to you?

Home is wherever you put your clothes at. Your hat, your coat, your bed your covers. It could be out in the woods. I really don’t care where I’m at.

Has being houseless affected your faith?

I’ve had faith in God since I was seven. Faith is what’s inside you, and you believe. You’re born you live, you go to God. It’s perfect for everyone in there. It’s love; it's hope. God gives us love so we can learn.

What would you say to people to help them understand houselessness?

We’re just as good at being human beings here as they are at home. We’ve got to walk all this way just to shower and eat. If it wasn’t for people like Kerry Ann and Darcy, we’d be out dying in the streets like a friend of mine that froze to death. Some are a bit handicapped and need medicine, and if they don’t get it, they go crazy. Every time this one lady starts yelling, I get dizzy. But everyone here is good people. They just have a bad life. Like one guy tried to commit suicide down by the river yesterday. But some people talked him out of it and stuff.

How would you like to see houseless people treated in the future?

I’ve been to lots of places, and I’ve never been treated worse than in this town. Treat us like you want to be treated. With respect. Help them. Love people, even the hard ones.

What’s the best thing that happened to you this week?

I stayed home. Did the housework. Peace and quiet that day. The best thing that ever happened to me? The day I quit drinking. I don’t drink, just coffee, water and tea. I don’t smoke pot.

Where would you like to be in a year?

She laughs.

You know I had a chance to get married to a guy and move to Hawaii? Hmm, where do I want to be in a year... Well, that’s crossed my mind many times, but right now I wish I was with my mama in heaven. I know I’m going to die someday, but I’d just like to be at peace with my mother. It’s been seven years since her death. Money doesn’t matter. It does not bring me back my mother. She took care of us, and nobody can ever take her place.

We talk for a little while longer and then I give Diane a $10 gift card for Safeway for sharing her story with me and thank her for her time talking to me. She leaves, closing the door politely behind her.

Pictured: Inside the pallet shelters are very utilitarian but make good use of the small space.

Staring at the door, I found myself itching to go outside, out of the small white and now silent room. When I do, I find some of my new neighbors getting ready to leave. They’re a couple, man and wife. And one woman has recently had surgery, and she hops around on crutches, moving slowly. The man tells me that the dog they have with them is his wife’s service dog. I ask if I can interview them and maybe take a picture of their dog, but they are on their way to go have dinner with her parents at the moment. So, I say maybe I’ll catch them later and leave it at that.

I texted my partner and ask her to pick me up for dinner. When we sat down to eat I discovered that the cold had made me extremely hungry.

When she pulled back up to drop me off, I saw her eyeing the strangers standing along the concrete barriers smoking with some concern. I saw the exact moment she realized that she was about to leave me in unfamiliar territory with complete strangers. I also realized she hadn’t spent all afternoon trying to get to know these people like I had, and there was a touch of concern in her eyes. I assured her that I was going to be just fine. We stared off into the night for a moment. In front of us lay the pallet homes, like straight white teeth, lined up in orthodontist approved rows, clean and stark. All around the edges of the lot dark figures wrapped in blankets and coats lean up against concrete barriers, smoking cigarettes, chatting amongst one another. Such a view from the outside can be intimidating, especially when you intend to approach it. But still, I felt no fear. Instead, I felt I had to get closer,

I promised to text my partner goodnight before I go to bed. As I stepped out of the car with a blanket under one arm and a GoPro camera under the other, and I began to walk towards those unknown faces and names, I wondered what I would learn. I wondered how an onlooker might perceive us as I got out of the car, me in my favorite sweater with the hole in the shoulder, and a cheap poly blend fleece blanket - the kind you keep in your car for emergencies under one arm. Would they see a journalist? A non-binary person? A vaguely transgender man? An individual? Or simply assume I was a houseless person?

Pictured: A view of the Pallet shelters from the corner of Bargeway and Terminal at dusk on Jan. 20.

As I walked up to my home away from home for the night, I introduced myself to the first guy I saw on my way. He introduced himself as Harold. He listened to me talk and declined to be interviewed. Instead, Harold flips the script and proceeds to interview me! He proves to have quite the natural instinct for investigative journalism and embarks on a mission to find out what I’m all about. Harold so impress me with his skills as an interviewer that I tell him so and he responds that he ‘has a gift’.

In response, I ask him if he’ll write a piece for CCC News and I hold out my business card.

Funny how moments ago in the car I was thinking about how hard it can be to start a conversation with a stranger but how doing so, easily changed any anxiety I had into curiosity.

Pictured: Cole Goodwin, settles in to the houseless shelter. Looking a little flushed from the warmth of the heater after having been outside in the cold all afternoon.

I turn in for the night.

Inside my tiny home I set up my workstation- MAC laptop, water bottle, double and triple checked I’d brought a phone charger. Not a bad place to spend the night I thought. Electricity is a gift. I took off my shoes and had just started to get comfortable on the bed when I hear someone yelling something only half intelligible about serial killers outside. Now it’s a little alarming to hear someone yelling about serial killers only a few feet from where you intend to sleep for the night. But, surprisingly, I still felt pretty safe. Perhaps what was more alarming was that nobody seemed to be going outside to see if the person yelling was okay. So I put on my shoes and coat to go investigate. Then I heard someone yell at the yeller to “STOP IT.” The yelling stopped. And several door slams later quiet resumes.

But since I’d already gotten dressed I decide to step out into the night. It’s cold. And no one, not a soul was out, smoking a cigarette, yelling or otherwise. I stand by the dumpster sat only a few yards from the camp and look around. I think maybe I said out loud “Is everyone all right here? Is everyone okay?” Nobody responds, because there’s nobody there. I decide the action must have subsided for the night and go back inside - although I don’t take my shoes off just yet.

Two minutes later, I text my partner that I’ve settled into my pallet shelter and send her a photo to reassure her I’m toasty and warm.

Pictured: Cole Goodwin, gets cozy and settles in to the houseless shelter for the night.

I started to wonder, as I prepared to sleep so near to people that others would cross a street to avoid passing by too closely on the sidewalk... What is it about seeing a person sitting on a street corner that raises alarm bells and fear in so many? What is it about a person simply living outside, or in a tent, or in a temporary tiny home like these that can create so much fear?

Moments after I picked up my computer again, a person came knocking on my door. Curious, I opened the door, and outside a pair of wild eyes met mine. The person asked me, “Do you have a cigarette?” I couldn’t place the expression exactly on the person's face, but I think maybe you could find the same look on my own face on a bad day around 2 PM when the world has come tumbling in on me, and I find myself desperate to find some peace. I made a mental note: perhaps this was the interaction that people so feared, this emotional openness, this naked need. The type of need that can be difficult to look at directly in the eye, dead on, with a courageous heart and say- ‘I see you, I will not look away.’ I didn’t have a cigarette. But I asked them if they were doing okay, and they froze for a minute, unsure of what to do next it seemed. After a moment that felt like an eternity, they responded, “Okay,” perhaps a little nervously, and took off to look elsewhere.

Pictured: The river view from the Pallet Shelter lots looks out at the industrial district lights.

I had to pee, so I decided it was as good a time as any to try out the porta-potties provided. After using the cold, dark, unlit porta-potty, I went to stand by the fence in my sweatpants to watch the lights of the city and the steam rising from Google data center on the port. I could hear rainwater pouring through a nearby drain. It was peaceful and kind of nice in an urban camping kind of way. While I stood there again, I thought about how a stranger in a passing car might see me in that moment. A person in their sweatpants standing down by the river? A journalist looking to find the bigger picture? Or would there be other assumptions? Would they perceive me as a houseless person from a distance? How would that make them feel? Perhaps it was these questions more than anything that helped me to confront my own privilege in the moment. Because despite each human being a unique individual, somehow humans still seem to believe they can interpret a person's entire being based on nothing but their aesthetic.

I went back to the shelter and tried to create some additional privacy by covering a few of the windows, but the slippery styrene walls and minimalist design of the shelter’s interior made it difficult to do so. I wondered how other people had managed to cover theirs. Slightly bored, I tested the emergency exits, opened the windows, tested the plug-ins and breakers, just to see. Everything worked perfectly. Eventually, sleepiness won out around 2:30 AM. I found myself dozing comfortably, the window cracked just enough for me to listen to the sounds of the night - the gentle rain and the hum of the heater. It’s enough heat to keep me cozy as I sleep soundly and peacefully.

Breakfast with Community Meals, St. Vincent De Paul Society

The next morning I wake up warm and cozy with the sunrise, to the not so beautiful sound of reversing forklifts and semi-trucks. My body felt relaxed and rested, so I got up and headed to St. Vincent de Paul Society. Several people staying at the Pallet Shelters were already enjoying a free community meal there, taking showers, and doing their laundry. However, unlike me who elected to drive over there, most walk, carrying whatever they need with them.

Walking up to community meals, I saw the familiar scene of people milling about, leaning up against the building, sitting at the picnic table. But to my deep relief, I felt as though I was seeing it with new eyes. This was not a frightening band of strangers, for amongst the crowd were the faces I’d seen in the Pallet Shelter community, the voices I’d heard in the shelters next door to mine, the people who I’d slept only a few feet away from, people I’d only just recently come to know by name.

Pictured: Nick Lowe, Austin Kalista, and Keith Bright

No longer did I see people I didn’t know just seemingly hanging out doing nothing. Instead, I saw people who were waiting to eat, waiting for their shower time slots, waiting for their turn to do laundry, and waiting to use the phone or the computer. Just people, just waiting and hoping that they’ll find someplace warm and dry to sleep tonight. I spot Keith Bright, in the crowd, who I’d interviewed the day before.

“Hi Keith,” I say.

“Hey,” Keith said back, looking a little surprised but not unhappy to see me. The circle opened up to make space for me. Several interested eyes looked me up and down. I introduced myself to the people who didn’t know me yet-and ask if I can take a picture. Several people stepped away the moment the camera appeared but those that remained struck a pose. I asked if they know where the entrance is, and someone points to the door.

Inside the door I could see that the place was busy. It’s overwhelming at first, and my eyes don’t know where to land, where to look. The walls are a hodgepodge of thumbtacked PDF’s and handwritten signage. Some posters explain rules, others services, some are promoting equity, while others declare that Jesus loves you. A volunteer named Linda Huteson, was busily putting food out and wiping down tables, trying to keep things COVID-19 compliant. I saw donated Bakitchen doughnuts, soups and chili dogs. People were doing their laundry. Diane was sat at one table with some food in front of her. Another man was sat at a table reading a book. Someone was using the computer, and a blue-haired woman who seemed to work there and who later I would learn was the famous Kerry Ann I had heard so much about from other residents of the Pallet Shelters seemed to be running around everywhere, directing the traffic. She popped in and out of the office, helping people use the phone, asking people to put on their masks, telling people to wait their turn for their laundry slot. I heard her say, “Hey there are no weapons in here,” and take a hunting knife from a fellow in a straw hat who I’d learn was named Jon Bon Jovi.

Pictured: Linda Huteson, a volunteer at St Vincent de Paul serves breakfast and wipes down the table for COVID-19 compliance.

Interview with Dave Lutgens, Executive Director at St. Vincent de Paul Society

After a while I spotted Dave Lutgens, Executive Director, and St Vincent de Paul Society board member of 25 years coming over to talk to me. He’s well set in himself and talks in a deep voice with an even “this is how it is” type tone. We sat down to interview, but it was chaotic and our conversation often gets interrupted and heads on tangents as people come and go.

Pictured: The laundry facilities at St. Vincent de Paul Society include one washer and dryer. Houseless people can sign up to use the laundry.

He ran me through the basics of their finances. They rely on donations and on renting out a building to the St. Vincent de Paul thrift store on ninth Street in The Dalles. And he tells me about the many services they offer: laundry, showers, emergency housing, auto repair, clothing vouchers for local St. Vincent de Paul and Salvation Army, job connections, and more. “We try to get them what they need. We walk the fine line between helping them and enabling them,” he tells me.

“A year ago in January they counted 186 homeless people in Wasco County,” he said to me. “Here we see an average of 40 to 50 people.”

Pictured: There are two shower and bathroom facilities at St. Vincent de Paul which houseless people can sign up to use.

Up until this year, St. Vincent de Paul Society had also been home to the warming place, but they couldn’t swing it with the new COVID-19 regulations.

They would usually put up to 19 cots in the room where we currently sat.

“We could house 14 to 15 a night. But with the new social distancing required, we could maybe put in six or so,” Dave continued. “And we work with volunteers, most of which are elderly. We told the city early on that we would not have a warming place this year. Their expectation was that non-profits were going to step up and do this, but it’s just beyond our scope of what we’re able to do. So, I think that part finally got the city convinced that they should do the tiny homes.

What do you think about the pallet shelters?

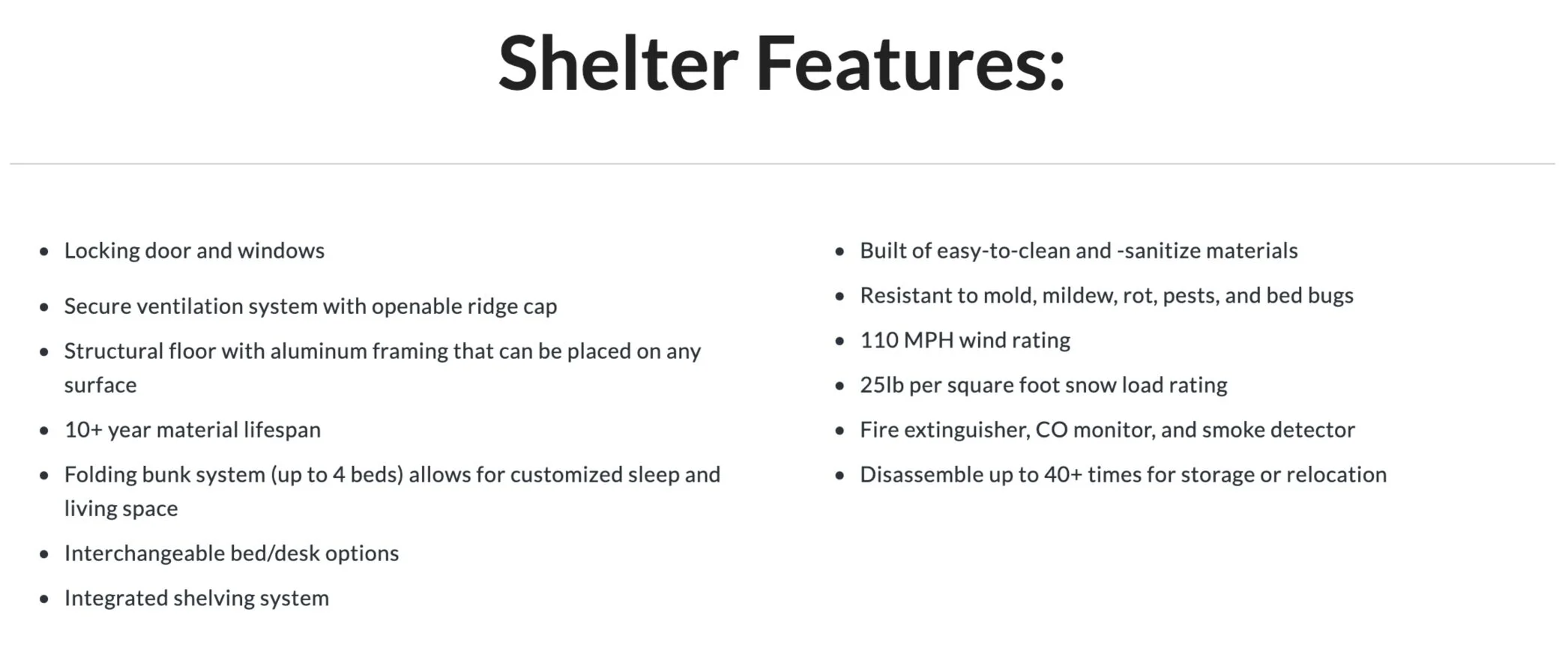

Source. The visual differences between the Pallet Homes and SquareOne Villages are instantly obvious. Trees, plants, gardens, and brightly colored shelters are in stark contrast with the utilitarianism of the The Dalles shelters which sit on a bare gravel lot.

As of now the Pallet Shelters are only scheduled to be used until March when the weather warms up. Dave told me that he hopes the city will consider leaving the Pallet Shelters up year-round and not just in the winter when it’s cold. A view many experts also have expressed, saying that houselessness is tremendously difficult to come back from and that solutions to houselessness require long term solutions and investments.

“They need to have people in there permanently year-round. We need a place like that we can get serious about and that can be managed better. Start with baby steps. You don’t need to build $100,000 apartments for people. Do the pallet homes, and from there start trying to get these people into jobs. Eugene has tiny homes (SquareOne Villages), and they got a bunch of contractors to donate one, and they put this village together, and they have a common kitchen and bathroom area. And there’s another one that is for people that work. They pay three or four hundred a month for their space. They can stay there for up to two years while they get into regular housing. And part of their money they get back for their first and last month's rent to get into another unit. They put them to work developing work skills. They go to renter school, and then they also can go to owner school and learn how to rent to own.”

Source. Pictured: A table explaining how two different types of SquareOne Villages work.

Dave starts to tell me about some of their success stories. “We have one guy (who is staying in the tiny homes) who’s working now. He comes in here after hours to shower. Tom was a bellringer at Christmas. We had another guy that had just gotten out of prison. We got him on his feet, he’s got a full-time job now and that’s fantastic.”

“Every individual is different. You know some have a little more push than others. Some have a life story that’s rough, and we also have some people that make some dumb mistake when they’re 20 years old, and they get some plea deal on a drug thing, and then they can’t get car insurance at a reasonable price or a place to live. And if they don’t have any job skills and experience already, they’re never going to get out of it. And we have one police officer in town. He’s a jerk who will do anything he can to arrest them.”

Pictured: Signage explains the rules of the St. Vincent de Paul Society shelter.

Someone kicks over a chair. Dave looks over and says commandingly, “Pick it up John.”

John, looking slightly chastised, responds in a child’s voice, saying something along the lines of, “But it offended me.” He picks the chair up and puts it back.

Pictured: Signage outside St. Vincent de Paul.

“We offer more services now than we did, but, you know, we have the same problems we’ve always had, you know. We have neighbors that don’t like us. We’ve had to boot a few people that can’t follow the rules. No drinking, no drugging. This should be an island of safety for those that need services. Some days are pretty quiet and others are just- wild, full moon or whatever. But they’re not dangerous. They’re just happy to have a meal.”

What do you think drives “not in my backyard” attitudes?

Dave responds without hesitation.“Fear. A lot. Fear of the unknown, not knowing the people. I know I was very hesitant coming in here, you know. I had preconceived ideas too.”

I asked about the blue-haired woman who works there and is running around.

“That’s Kerry Ann. She works here. She’s the good cop; I’m the bad cop, ” he tells me. “She was homeless. She knows a lot of these people. She knows their heart. She’s a good judge of people. I trust her judgment. She’s very valuable. When you’re homeless you get a different perspective. She didn’t even know this place was here until she was just about off the street. That happens, people don’t know that we’re here. I see people all the time that I know are homeless, but they’ve never been in here.”

Interview with Kerry Ann Childers, St. Vincent de Paul Society Office/Shelter Host

I sat down with Kerry Ann Childers to find out more. She was a volunteer for two years before her and her mother got hired at St. Vincent de Paul Society. She now does just about everything there: janitorial work, serving food, hosting, helping connect people to services. She seems to be running from the moment she arrives to the moment they close. She’s about 50, blue-haired, thin and a bit nervous at first. She doesn’t seem to trust me outright, so we start slow. I ask her about her last name and she says she’d rather not say then changes her mind. I ask her about her blue hair “It’s a fashion statement,” she says her voice is high sweet and soft, not what I was expecting. “What’s it stating?” I ask.

Diane interrupts from a few tables over with an answer “Kerry Ann LOVE.”

Pictured: Kerry Ann Childers hard at work, looking up a quote for replacement auto parts for a houseless person who’s car needs repair.

Kerry Ann relaxed a little at that. “We’re all family here. I care about everybody here. I don’t think there’s enough services for them. People down here are wonderful, and people don’t see that because all they see is the crazy or the ones that can’t help it. People don’t know these people until they come down here and work with them, you know, and see that they’re just people too. They’re people down on their luck, and they get treated so bad sometimes, you know. I’ll tell you what, it’s a hard, hard path to get out of that situation. But I did. I wanted to be an inspiration and prove that it can be done.”

“There’s a lot of love here. It’s sad because there are not enough resources to help these people. It feels like they just want them to go away. But if they ever got to know any of these people beyond just seeing them on the road or whatever, they would see there’s a lot to love.”

As we talked we are interrupted by a yelling match breaking out in the laundry area.

Kerry Ann has to get up and deal with it. She puts herself between the two men, physically distancing them and holding one back. I ask if she wants help; a few people tell the man to calm down. Kerry Ann stares him dead in the eye and says something I can’t hear, and he takes his stuff out of the laundry and leaves to go cool off.

After a moment Kerry Ann returns. I ask her if I could have supported her better in that moment. She laughs a little. “No you’re fine, It doesn’t usually turn into fights. I’ve gotten hit before, but it was an accident; they meant to hit the person I was holding back, and I got it. Most of the people don’t fight like this very often. I mean, we have a few people that come in here that yell around. I’m sure you saw some of that last night, but those are some of the people who need help.”

Kerry Ann tells me she’d like to get training on how to better handle mental illness and de-escalation. “We’re not exactly trained to be dealing with people like that, so deescalation classes would be good. It usually doesn’t get past the yelling part. I just don’t want people to get hurt. I had a brother with schizophrenia, so I can deal with a little bit of stuff. People used to say that my brother was faking it, but he wasn’t.”

Kerry Ann was also quick to say that not every person yelling on the street is schizophrenic. “Some just want attention,” she says. “Others need help and don’t know how to ask. If they’re wanting attention, if they need it, they’re going to get it one way or another, whether it’s good or bad.”

Kerry Ann’s brother died while houseless four years ago. “They found him in the river. He was in the river for six months. They said he died of natural causes. But they found his teeth under a rock. And a lot of people know what happened,” she breaks off, choking up a little.

I asked if she suspected violence lead to her brother’s death. “I know there was. Yes. I work here. I hear a lot of things. There was people that wanted to come forward but people moved around and phone numbers changed and... I think it’s sad cause it’s ‘just another homeless problem, and nobody thinks about the family or about everybody else in here that it could happen to.”

Kerry Ann’s story about her brother is not unusual. Quite the opposite. The deaths of houseless people and violence against houseless people are often insufficiently investigated or dead-end due to lack of documented information and witnessess moving around and having their phones stolen and number changed. I thought about Diane’s friend who froze to death, and the houseless person who had contemplated taking their own life only a few days ago down by the river. There was so much death here. The houseless people in our community seemed to be living with it breathing down their necks every day.

When I asked Kerry Ann how she hopes to see houseless people treated in the future she says she still has hope. “Things can change. People can change. I’d like to see some inspiration instead of judgment, some understanding instead of being talked down to.”

We started talking about the work Kerry Ann has been doing to try and create that change.

Do you remember the day, not that long ago, when the houseless community had a car wash over on Pentland and West 2nd St in The Dalles? It was near The Dalles Chamber and the St. Vincent de Paul Society Ministry Office and Shelter?

Kerry Ann does. She was the one who organized the car wash.

“One of the first things I did when I started here was a car wash,” Kerry Ann said. “To get them to mingle with the community so that they could see that they’re just people too. Just down on their luck… They’re not as crazy as they think; they’re just maybe dirty because they slept on the sidewalk or didn't have a shower, or a way to do their hair.”

Kerry Ann started to get a little teary-eyed, as she continued, “And, uh, I couldn’t really get anybody to do the car wash.”

I was saddened to hear that not a single person went to get their car washed by the houseless that day. I could remember debating about whether to go get my car washed. To my shame, I remembered how the sight of a shirtless man holding a sign had triggered anxiety in me. I’d felt terrible about it, I’d debated with myself, but I hadn’t gone. I could remember it very clearly now. And now that same man, who did not wish to be named here, was now sitting only two tables away from me, eating breakfast. In the end, Kerry Ann’s friends were the only ones who came to get their car washed that day. I wondered if my guilt showed on my face as Kerry Ann continued, “So I called in friends, who called in friends. We raised some money that day-and all that money went back to the people here.”

We talk for a little while longer. Kerry Ann wraps up our interview by telling me a story about how at one point her rent went up, and she was at risk to lose her apartment.

“These people are homeless, and they took up a collection for me, so I could keep my home. And I said I can’t take this money from you guys. You’re homeless, and I got a home. But you know, they couldn’t exactly give it back, and so I took it and I kept my apartment.”

I thank Kerry Ann for sharing with me, and she goes back to work.

Pictured: Dan Lutgren makes a phone call while Kerry Ann Childers tells Jon Bon Jovi that community meals is closing soon. Jon Bon Jovi grabs his bag and dinner to go.

That’s when I meet Jon Bon Jovi, a self-identified permanent traveler, who’s been all over the United States and who is more comfortable roughing it in the woods than urban camping. He’s not used to being so low on funds he says.

An Afternoon with Jon Bon Jovi

Jon Bon Jovi had walked four and a half hours from his camp on state property in order to get into town and to the community meal that morning. When I tell him I’m a journalist writing a story about what it’s like to be houseless in The Dalles he tells me he likes my journalistic integrity and agrees to an interview.

“I trust individuals. If an individual wants to know the truth, I have no problem as long as they're willing to swallow it. I'll give them the truth.”

Pictured: Jon Bon Jovi posts up outside the entrance to Community Meals.

I ask for his name and he says, “John Bon Jovi. My first name really is John. Bon Jovi's the last thing I'm gonna give you okay, so I'm a permanent traveler. I'm a nomad. I travel. I've been all over the United States. I've been to Pennsylvania. I've been to Florida. I've been to Ohio, Tennessee, Kentucky, Michigan, South Dakota, Montana, Oklahoma, Colorado, and now Washington. I travel where the wind blows, and I like the open road. I travel where work is going.”

“Normally I'm not broke. I'm not a broke individual. COVID really put a damper on my lifestyle. So work was really hard to come by while I was traveling. Normally, I would hitchhike or I usually had a vehicle. But because I didn't have any money I couldn't maintain it. I originally had a motorbike. Couldn’t maintain it. So I had to sell it for what money I have. I got on a train and came here. I left Michigan because I don't really like big cities. Normally when I go to a big city, I am only passing through. I'm not gonna stay. I come to the city to get supplies, and I don't really like big skyscrapers and stuff like that. They unnerve me. So, I came here because, you know, I was told there is work here. That's pretty much why I'm here. You know COVID really took a number on it. I understand that people are afraid of this virus, you know, especially if you can't see something you can't fight it. But shutting down every business. It's not, it's not something I think is good for a community as a whole. When you shut down the only thing keeping the economy together, it really hurts things, and you wonder why there are more homeless people in the streets. Well, maybe this is why.”

“No human being has a greater claim over your life and property than you do. But governments don’t see it that way; they want control over absolutely everything they can get their hands on. You need a license for this; you need a permit to do that. I have a big problem with how governments really overshoot their authority.” he concludes.

“When I first came to this area, I was staying in Klickitat, at a stewardship forest that was a non-profit organization, and I was working there. I got up every morning. I was there for like month and a half. I would get up every morning and feed the pigs and stuff like that to pay my dues there. The owner wasn't really worried about it, but I went to the owner, and I told him, I said, ‘hey I can’t be here without any money in my pocket.’ And he said, ‘alright, you’re welcome to come back if you want.’ So I headed off to The Dalles. I’m mainly a laborer. I got a lot of skill in farm work; I’ve worked in restaurants, diners, construction, stuff like that. Just hands-on-stuff. I’m a very capable individual, and if someone gives me a task, I perform it.”

Interested in hiring Jon Bon Jovi? Give him a call or send him an email at: 509-257-8381 or DarkDuby150@protonmail.com

“People are getting backlash because of these tiny homes, but how is it hurting anybody? Why are they getting this push back? Fear? Fear of what? It doesn’t hurt anybody. I think that catering to fear only makes things worse. We need to do things a different way. It strikes me as just really ridiculous. I've been all over the United States, and there are some good places, and there are some bad places. This is a really nice place according to what I've seen so far. And I don't think they want to turn it into a bad place. I identify as a nomad, but I’m willing to take the housing in order to make some money until I can get some better camping equipment. I want to get a bigger tent, maybe a generator.”

Pictured: Jon Bon Jovi poses at his campsite on state property near Rowena.

He continues to tell me more about himself. “I enjoy the outside. You know I complain about how far my camp is from town, but when you lay on the grass at night and you can see every constellation. It’s kind of worth it. I like to live closely with the land.”

I ask if I can give him a ride to his camp later and take some pictures. He eyes me a little “Normally I wouldn’t tell anybody where my camp was, but I don’t think you have any ill will.”

We talk a bit more and we agree to meet up later so I can give him a ride to his camp, which he intends to break down for the night and then come in closer to town.

I ask him what he thinks people see when they look at him.

“People look at me and automatically assume I’m a bum. I’m really not. I like to work. I enjoy working. I don’t have a disability. This is the first time I’ve had food stamps in seven years. I got it out of necessity, not because I wanted to. I normally have money in my pocket for food, and if I don’t have money in my pocket, I’m pretty sure there’s a rabbit around somewhere.’

Pictured: Jon Bon Jovi shows me how to use a flint to make a fire. But it’s so wet out that we fail to make a single spark.

“I grew up in the woods. I remember when I was 12 years old; I told my dad ‘no’ for the first time. And he looked at me and he said ‘What?’ And I said ‘no’ again. And he said, ‘okay.’ The next morning, he got me up at 5 AM and said, put some gear together. When he says put some gear together, it means, we're going out to the woods and come with me. So he’s like, since you are old enough to tell me no. You're old enough to fend for yourself. And he left me in the woods by myself for two weeks. I was 12 years old. He came back two weeks later. I had a cabin built by myself. I built a fireplace out of stone. Right in the middle of the woods. I had smoked meat hanging up. He's like, you know what? I'm very proud of you for this, but don’t ever tell me no again. Just do what I tell you to do. He laughed, but he said don't tell me 'no' again. So he meant it as a punishment, but I enjoyed it. I loved it. There was a creek nearby and it was summertime, so it wasn't winter so I wasn't gonna be cold. I would jump in the creek and wash off. I made candles out of deer tallow.”

I was enthralled by this larger than life story, I asked him if he was ever scared.

“No never. Because in the woods you know what's coming to get you. You know, it's gonna be a wolf, a bear or a cougar, but in the city you don’t know who’s your friend and who’s your foe. Animals normally leave humans alone; they don't just go and attack human settlements for no reason. The only time they're gonna attack you is if you’re encroaching upon their territory or you're a threat to them. Normally. I had one issue with wolves around my area; I threw them scraps from the deers I got as a peace offering and they left me alone.”

He also tells me about the time he came face to face with a cougar in his own tent. But it’s such a good story I think you should hear him tell it yourself. If you see him around. Why not ask?

It’s getting to about lunchtime now, so I tell Jon I’ve got to go get some lunch. He goes and retrieves his hunting knife, which Kerry Ann had taken earlier under the no-weapons policy, and I give him a ride to the store.

He tells me he’s hunted wolves in Canada and says that “Normally I try not to hunt predators. I only hunt deer. I can hunt a deer I can quarter it. I don’t hunt for recreational purposes. I hunt because I’m hungry. I’ve been paid to teach wilderness survival skills. I live really close to the land and stuff like that. I just enjoy that. I don't really like grocery stores. They don't really have an appeal to me. The earth provides me with everything I need.”

“Governments have created this bureaucracy where it's necessary for you to go get a nine-to-five job necessary for you to pay rent and you're paying all of this money, You have no time to just sort of enjoy your life because between rent and insurance and all kinds of other stuff. I spent six months in Manhattan and wanted to kill myself. I was genuinely suicidal, but I was up there for a construction job. I could not stand it. I couldn’t see the stars. Everybody was screaming at 3 AM. I couldn’t do it. And on top of it you walk down to Times Square and there’s trash everywhere and the people were so rude.”

At the store we split up. He goes to buy some chewing tobacco, and I pick up lunch for myself. My brain is swirling with all the stories that I’ve heard over the past day, some of which I’ve gotten permission to share and some of which I’ll have to keep between me and the person I spoke too. I realize I’m looking forward to a moment to myself to write some of it down and have chance to share them.

After the store Jon Bon Jovi and I head over to the Pallet Shelters to see if he can get in there for the night but Darcy has taken the afternoon off and the new volunteer seems unsure about whether there are any vacancies. I know there are vacancies, including the shelter I’d stayed in the night before, but she can’t let him in without the proper paperwork. I turn in my key to her. She is friendly enough, but I sense Jon starting to get a little anxious about where he’s going to stay for the night. Eventually it becomes clear he will have to find somewhere else to spend the night and he agrees to come back tomorrow to check it out again.

I drop Jon Bon Jovi off at St. Vincent de Paul with a promise to come back and give him a ride to his camp later.

I pick him up after the dinner meal has been served. He thanks me for actually coming back. We hurry out to his camp to break it down and take some photos before dark. I’m trying to stay chipper but I’m tired now from my long night and day following around TD’s houseless community, so I’m a bit quieter than before but he doesn’t hold it against me.

He directs me to his camp which is near Rowena.

Pictured: Jon Bon Jovi packing up his camp for the night.

He takes me to see it and when we get there, I see that he, indeed, has a gorgeous view from his camp.

He's camped on a bluff, a flat spot above the freeway with a gorgeous scenic view of the hills and river. It’s not his usual spot he says, he says he doesn’t like camping near a road but it is camp of necessity. The wind has blown some stuff about but together we quickly pick it all up. He has very few belongings. He shows me what he’s got. He has a tent, a few blankets, a laptop and camera, a flint stone, and cooking stove made from a tin can. He tells me his laptop runs on Linux, he can’t stand Microsoft’s operating system. He shows me how to use the flint.

It starts to rain, so I start to help him get things loaded into the car before they get wet. Despite not having much, it takes quite a few trips back and forth carrying stuff to the car.

When we’ve broken everything down, we head back into town. We drive around looking for another spot for him to camp, but what we do find makes him anxious. He’s not used to urban camping he says and he’s not interested in camping on the sidewalk. He’s used to the woods and having money in his pocket. He asks if I can get him a hotel for the night. I agree to it, but my phone has died, so we have to stop at the bank so I can check if I’ve got some extra money to spare.

Pictured: Jon Bon Jovi warm and dry at the Super 8 Motel in The Dalles.

We pull up to Super 8 Motel near Fred Meyer, and he tells me that he doesn’t have any ID. So we’ll have to put the room under my name and on my card.

We go inside and make some small talk at the motel check-in. “Promise not to trash the place?” I say.

“I promise,” he says “And I always keep my promises.” He also promises me he’ll find a way to pay me back. He says he feels bad. But I tell him I’m not helping him because I want him to feel bad. I’m helping him because it seems like the most human thing to do. After all, he’d been sharing his story with me. I wanted to give him something in return. So I tell him not to worry about it. “Just send me some good vibes through the force.”

Later he sends me a picture of himself enjoying the comfort of the hotel saying, “Thank You for what you did for me today.”

Coming Back Home from a Night and a Day in the Life

I try to feel something, but I feel totally drained.

I drive home, tired, not having showered in 24 hours, exhausted from the weight of so many stories, people living on the edge between life and death. Survival and joy. The drive is a blur. I keep replaying the night and day’s events in my head.

When I get home, I see my partner and our apartment for the first time in 24 hours.

It almost doesn’t feel real.

But when my partner hugs me, deep relief and gratitude floods through me. I suddenly realize I'd been in a place of such deep empathy that I had kind of forgotten that I had a home. It might sound stupid, but I literally thought to myself in that moment, “Oh yeah, I’m not actually houseless.” I have a place to sleep. I don’t own a house, but I have the ability to rent one. I have a loving partner. I have two dogs. I have a place where I can leave all my bedding and cookware and shampoo and all the other many things that make up the house having lifestyle. I have a home.

And I realized that I’d succeeded at what I set out to do: to find out what it’s like to be houseless in The Dalles for a day, by asking questions and listening to what I heard. It wasn’t what I had expected. There was a community there, support, and of course, there were plenty of traps and cracks to fall into and through, but my privilege as a housed person had mostly insulated me from any real danger. The people I’d met had impacted me deeply. A mix of emotions bubbled inside of me. There I was in my home, and yet on the streets tonight in my own home town people were shivering. People were hungry. People were hurting. I silently gave thanks to people like Darcy Long Curtis and Dave Lutgens and Kerry Ann Childers who are doing the work to help. I vowed I would find my way to help as well.

It had been 24 hours since I was home or had seen my partner or the dogs, but I was still in a haze, lost in my thoughts about the transformational experience. I told my partner, unsure if I’m interrupting, unsure if she's been talking or not, because I’d been lost in thought. “I’m going to help these people. I don’t know how yet but I have to. We all have to.”

That night I take the dogs on a walk through the woods.

It’s snowing, and I’m wearing nothing but my underwear, a sweater and my boots. And I realize that the cold doesn’t bother me as much as it did even a day ago. Not after having spent so much time outside in it. I start to run through the dark snow-covered trees making a big loop around the property until I see the golden light streaming from our cabin windows again. Standing there in the dark with the shining light in the distance, I say a silent prayer. Sending it up into the night sky. As I walk up to my front door, every footprint I leave in the snow reminds me that a better future happens one step at a time. We just have to keep putting one foot in front of the other until we start moving forward.

The next day I go to work and it is absorbing, I have so much to catch up on after having spent just one day in the life of a houseless person in The Dalles. I can’t even imagine what it would be like to come back after a week or a year.

Jon Bon Jovi texts me to let me know he’s made it out of the hotel okay and that Darcy is going to help him move his stuff into one of the Pallet Shelters with a new roommate. He hopes to apply to a job at Precision Lumber and tells me he’s put in an application at Super 8 Motel. I smile to myself a little. Glad to hear some good news.

I decide to swing by Community Meals to say hi to my new friends and I just happen to run into Rich and Rose Mays volunteering in the kitchen. I talk to everyone, say hi to Jon Bon Jovi, he shows me that he’s repacked his backpack so that it actually holds all the stuff-no more making four trips to the car. My conversations with everyone are easy and light. Something about it all just feels right, and I feel good knowing that I’m going to be writing some ‘news’ myself about the whole experience very soon.

Pictured: Mike and Judy Makela and Rich and Rose Mays from Gateway Church volunteering in the kitchen at Community Meals.

What I've learned from this experience is this: Get out in your community. Meet the people who are there. Look them in the eyes and acknowledge that there is an awake human being sitting across from you. And you may find you can no longer turn away from their struggle, because you may find there's something there that you've been missing this whole time: a human connection that transcends any stereotype. I know that what I’ve found here was not a scary, drug-filled, crime ring, but a loving, giving community struggling to survive on the edge of our house-having society.

Here are some ways you can help

Donate

Donate to The Dalles Winter Warming Shelter online

or by mailing a check made out to

Darcy Long-Curtiss, PO Box 4, The Dalles, OR 97058

or

YWCA of Greater Portland

4610 SE Belmont St, Portland, OR 97215

and note on the memo line that it is for The Dalles Winter Shelter Site (TDWSS)

Donate to St. Vincent de Paul Society by mailing checks to

PO BOX 553

The Dalles, OR 97058

Volunteer

Contact Dave Lutgens at St. Vincent de Paul (Community Meals)

541-980-9209

dave@svdpthedalles.org

Contact Darcy Long Curtis

541-980-7184

dlong-curtiss@ci.the-dalles.or.us

Source. Follow the link to learn more about Mid-Columbia’s Ten Year Plan to End Homelessness.