Universal Love and Foul Play: A Column By Nancy Turner

By Nancy Turner

Nancy Turner

Lots of families in The Dalles have backyard chickens. If you walk down the alleys behind houses, you’ll likely come across fenced enclosures, with chickens strutting their stuff. Within a three-block radius of my house on E 14th there are three chicken coops. Breeding, raising, and keeping poultry is permitted, but killing of animals is not allowed. The town rulemakers were concerned it would be too upsetting to neighbors. Another thing that’s not allowed is roosters. Nobody welcomes a Cock a Doodle Doo at 5 a.m.

According to local ordinances, chicken coops are supposed to be 100’ from the front property line and 25’ from the side and rear property lines. From what I’ve seen, this ordinance is not enforced, as long as people are respectful of their neighbors and nobody complains.

When I Googled “Chickens in The Dalles,” up popped KFC, Lilo’s Hawaiian BBQ, and Burgerville. I read the Best Chicken Vindaloo is at Bamba’s Indian Restaurant. Ok, fine. But that’s not what I was looking for. If you’re interested in getting live chickens, not cooked ones, check out Coastal, Mikes, Midget White, Zion Farms, and 7 Mile Farms. They’re only available seasonally, so call first.

Years ago my husband, Peter, and I agreed to take in a small flock of chickens from a friend who needed to re-home them. We had plenty of land surrounding our house in SW Portland and figured we could put the girls to work keeping bugs out of our vegetable garden. And there’s nothing like the taste of eggs from free-range chickens.

My seven-year-old son, Toby, and I decided we’d build a chicken coop. Even though Peter had plenty of power tools, I hated the racket. I decided to only use hand tools. For the frame, I bought 1×2s; easier for me and Toby to handle. We hammered and nailed a structure that looked more like a kid’s playhouse than a hen house. It was about three feet wide and about four feet long, big enough to hold nesting boxes and bars for roosting. The peaked roof was covered with shingles and just high enough so I could walk inside if I stooped over. We painted the exterior red with white trim around the windows to match our cottage-style house.

Once the area was enclosed with chicken wire, our friend brought over his birds.

I expected them to all be a warm brownish-red color like the Rhode Island Reds, but these were rare, exotic birds. Each one had her own unique mix of colored feathers, and personality. It’s been forty years since then, and I still remember their names. Henny Penny, Kentucky Fried, Little Pecker, Barbie (short for BBQ), Patty, Henrietta, Mother Clucker, and Chicken Little.

They became our feathered family.

Peter drove to the feed and seed store on SE Foster to buy chicken feed. That day the Department of Fish and Wildlife was giving away baby ducks in an effort to increase their population. Peter liked to think of himself as more responsible for the natural environment than the average suburbanite. He scooped up two fluffy yellow ducklings and brought them home. He saw them as more than just backyard entertainment. Once grown, they would be set free, maybe on a lake in Westmoreland Park. That was our intention.

Hello, World!

The baby ducks were too young to be put outside with the chickens. For a few weeks, we raised them in a cardboard box in the living room. Toby loved to fill the bathtub halfway and plunk the little guys into our porcelain lake. Like windup toys, they’d flap their baby wings, flip their foot paddles, stretch their necks, and dive. Without coming up for air, they torpedoed from one end of the tub to the other. We crammed into our tiny bathroom to watch.

Our wild ducks, also called mallards, quickly grew into adults. One male, one female. The male was friendly toward the female duck, but he also had a strange lust for one chicken in particular; Mother Clucker, our lovely, all-white hen.

This Mallard was eventually named The Bhagwan as the drake’s reign of promiscuity coincided in time with that of the religious leader near Antelope.

It was 1984. The Bhagwan’s religious commune in eastern Oregon was constantly in the news. One of the things the Bhagwan promoted was sexual promiscuity. When our mallard attempted to mate with Mother Clucker, she would shriek and squawk like nothing I’d heard before. It sounded more like terror than pleasure. We decided to name our passionate duck, (we spelled that with an “f) The Bhagwan.

“Yep,” Peter and I would comment to friends, “just another quack.” We changed Mother Clucker’s name to Sheela, after the real Bhagwan’s consort. We put out a metal wash tub full of water to encourage our Bhagwan to remember he was indeed a duck, not a chicken.

It didn’t help.

Elena in her element - basket in hand on the hunt for fresh eggs.

Our daughter, Elena, took special pleasure in collecting eggs. As a diminutive four-year-old, she could walk into the chicken house without stooping. Her Guatemalan heritage had given her soft brown skin, the same color as some of the eggs. The chickens liked her. They clucked and shuffled and allowed her to reach underneath their feathers, into the brooding boxes. Sometimes the eggs were still warm, with feathers stuck to them. They smelled of straw, chicken shit, and fresh air. With one hand grasping the basket handle, she carefully collected eggs, one by one. When all the eggs had been gathered, she put both hands tightly around the basket handle and proceeded, with slow, careful steps, across the yard, to the back door. Every single egg made it safely to the kitchen.

Chickens aren’t always nice. On summer days we often let them roam outside their penned area so they could eat bugs in the garden. Sometimes Elena liked to sit on the grass in the back yard, in a peaceful reverie, eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. One time a chicken dashed by her, grabbed the whole sandwich out of her hand, and ran off with it.

Elena screamed. In tears, she came running into the house, barely able to tell me what had happened. Her wide eyes looked shocked, but not angry. She wasn’t one to carry a grudge. “I just want to eat my sandwich!” she blubbered. I wiped her tears and made her another one.

Watching chickens go about their daily business of strutting, tilting their heads just so, to one side, then the other, and earnestly pecking at a particular spot, entertained me to no end. I could stand, leaning against the fence railing, and watch for long stretches of time. It was impossible for me to feel bad about myself around chickens.

I remember watching two hens peck at each other as they competed over one particular seed on the ground. There was a pile of grain just two feet away, but still, they squabbled. Sometimes one would shriek, run a few yards, stop suddenly, cock her head, as if she just had an important thought, turn around, and with slow deliberate movements, peck at the ground as she’d been doing before. I could find no rationale for this behavior. It seemed as if God had shown me that, compared to chickens, I was not as dimwitted as I thought. Most of the time they seemed happy, and so absolutely silly. I found their happiness contagious.

The little shelter Toby and I built kept our flock safe from predators. At dusk, the Bhagwan arched his neck, tossed his bill skyward, and quacked his evening call. It was as if he’d blown taps on the bugle. The hens clucked and muttered and scuttled into the chicken house. They squatted on the roosting rod or in a nesting box. The two ducks nestled next to each other in straw on the floor. Each bird tucked his or her feet beneath their rounded body and blinked translucent eyelids. Gentle murmurings, like quiet peeps, all seemed to be saying their last “good night,” “go to sleep now,” and “be quiet,” to each other. They waited for one of us to latch the door for the night. We did this every night at sundown, to keep them safe from raccoons and coyotes.

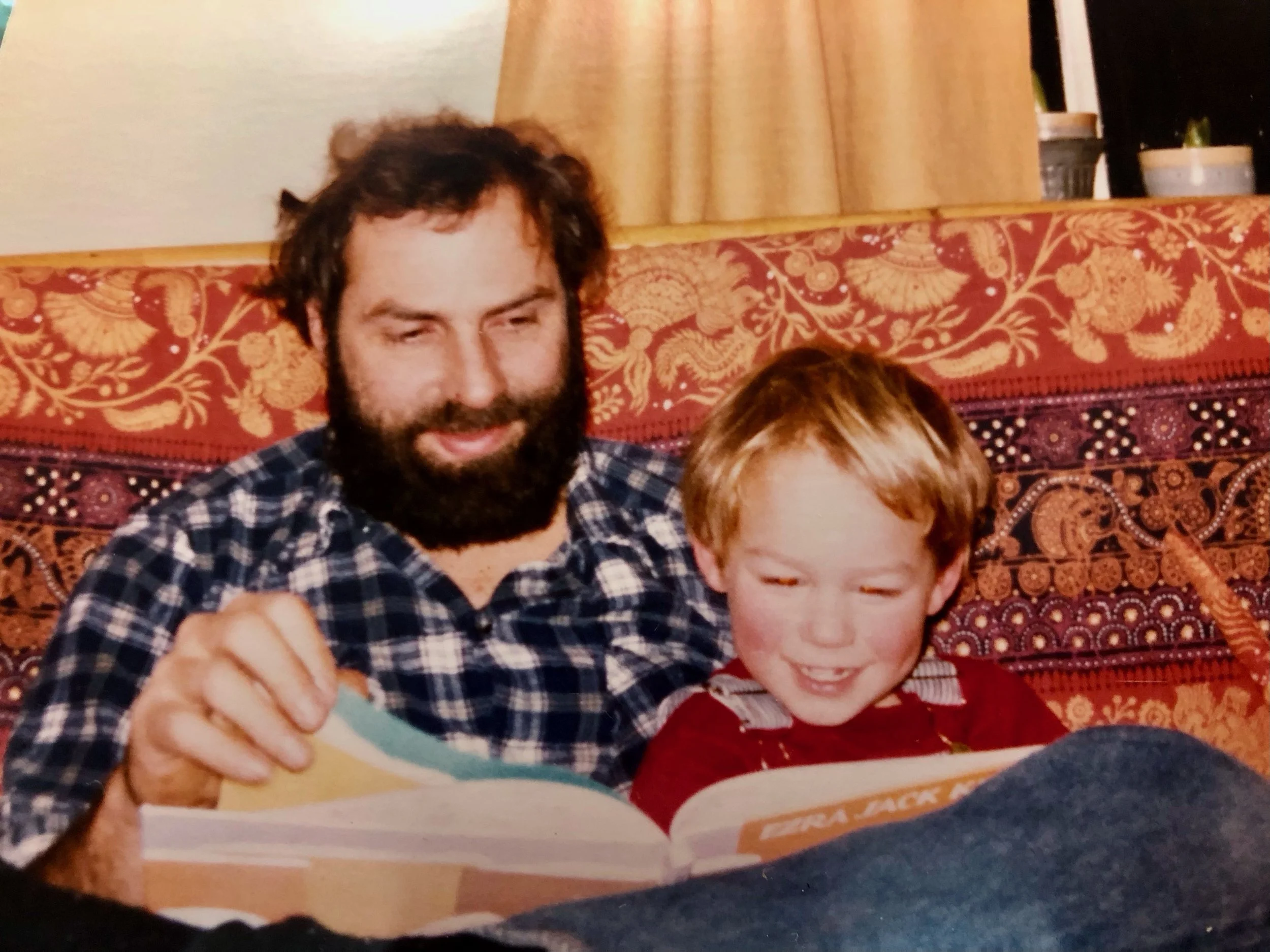

Peter and Toby enjoying a good book.

One warm summer evening, Peter and the kids were seated on the sofa. He was was telling a bedtime story. I was in the kitchen, washing dishes, absently gazing out the window at the garden, my hands warm in soapy water. Crashing through this calm family scene blasted the sound of frantic shrieking. I froze. The screams were terrifying.

Oh my God, I thought, the chickens.

I called out to Peter. We ran out the back door. The screen slammed behind us. It wasn’t dark yet. The door to the hen house was wide open. The air smelled of blood and panic. Sheela lay on the floor, her white wings in a contorted position; her head flopped sideways on the ground. The rest were wide-eyed and silent, not moving. I suppose they hoped that if they didn’t twitch they wouldn’t be seen by the intruder. The Bhagwan was missing. Gone. Not even a single feather.

Toby and Elena went to a window and cupped their hands around their eyes against the glass, straining to see through the darkening night.

I ducked my head and went into the hen house to get Sheela. I slid my hands slowly, cautiously, under her. She flapped her wing and folded it properly against her side. Relieved she was still alive, I carried her into the house and placed her in a cardboard box. She lay still, breathing, with her eyes closed.

“If she lives through the night I’ll take her to a bird specialist in the morning. She’s been badly bitten. A damn raccoon came early, before we got the door closed. It attacked the chickens,” I explained to the kids. Peter rummaged in a closet and grabbed his 22.

“Get a flashlight. I want you to hold it so I can see out there,” Peter barked at me as he raced outside.

Without thinking, like a soldier following orders, I did as told, and headed for the apple tree.

My flashlight illuminated thick leaves, small green apples and twisted branches. There was a sharp blast. A brown furry body tumbled and lay slumped on the ground. It was a raccoon, an adolescent.

I was stunned.

“Why’d you do that? Why’d you shoot it? You didn’t have to shoot it! You could have just scared it away. Now we have two dead animals,” I said, more as an accusation than a question. My body was flooded by adrenaline and guilt. I had been the one aiming the flashlight.

“I don’t know. What was I supposed to do? Jesus, it all happened so fast. The bastard killed our duck. And probably Sheela. Christ almighty.” He slumped down and sat on the overturned wheelbarrow, dropped his gun to the ground, and rested his forehead against the upturned palms of his hands. In this position, he wept.

Sheela survived the night. Peter and I talked it over and decided I’d be the one to take her to the vet while he stayed home with Elena. She seemed too young, for what, we didn’t know.

“Can I go with you, Mom?” asked Toby.

“Sure,” I said, “I’d like you to hold the box while I drive.”

In the examining room, I cradled our wounded chicken in my arms while Dr. Johnson, a bird specialist, examined her wounds. He told us that raccoon teeth carry a great deal of bacteria. Infection had already caused the two puncture wounds on her head to swell.

“We can give her massive doses of antibiotics, but, even with that kind of heroic attempt and expense, it’s unlikely she’ll survive. The wound is too close to her brain,” he said. Then he was silent for a long pause.

“Or, I can give her a shot to take her out of her misery. That’s the best I can do.”

Sheela fluttered her wing. Toby stood silent by my side, studying the man’s face. I twisted my arm to wipe tears dripping off my chin with my shirt sleeve.

“Yes, give her the shot.” I said softly. “I’ll hold her while you do it.”

I glanced at Toby. The summer before, when our cat cried in pain giving birth to kittens, he had burst into tears. He was a sensitive boy who cared deeply for living beings. He loved his pets. But now, with this silent and unmoving chicken, he stood quietly with a stoic stare, watching, not knowing what would happen next.

The three of us stood next to the examining table, not saying anything. Sheela didn’t move. Dr. Johnson shifted his weight, made a nervous cough, and looked down at the floor. Finally, he said, “You know it’s poison, right?”

I made an affirmative nod. I thought: Can’t he see that this bird is a beloved pet? Even though Sheila was merely a chicken, she was our chicken, and we loved her.

“Yes,” I said.

“Well,” he continued, “this poison goes into her entire body. If you eat...”

What did he think we were going to do, take her home and put her in a stew pot?

“I know,” I said, “we’ll give her a proper burial.”

Dr. Johnson administered the injection. The tender pulse of her final flutter brushed against my chest.

Toby and I got back in the car and I drove home. We were too stunned to talk. In the house, I opened the box so Peter and Elena could see Sheela. It wasn’t easy for Toby to explain to his sister what had happened. His throat wouldn’t let the words out. This was not like finding dead mice or snakes in the garden. This was painful.

“That vet is stupid. We shouldn’t have taken her there,” he said. “He gave her a shot and she died. She just stopped moving. She’s dead. I don’t know. She just died.”

“Did it hurt?” Elena asked.

“No,” Toby replied, “but mom cried.”

I lifted the box and carried Sheela to the backyard. Elena’s little hand clung tightly to my pant leg, just above my knee.

Peter got the shovel from the garage and dug a hole under the cedar tree, near where he’d buried the raccoon. Low branches brushed against his back, sending the smell of cedar into the warm air. Toby, Elena and I stood, and watched.

Peter said, “I love the smell of freshly dug dirt.”

Toby and Elena fashioned a bed of straw in the ground. I laid Sheela's limp body on her burial nest. Kneeling around the grave, each of us stroked her beautiful white feathers for the last time.

“I hope you had a good life. I’m going to miss you,” I said.

“I feel so bad about you suffering the last hours of your life,” said Peter.

“Your eggs were the best,” said Elena, in a solemn voice.

“You always made me laugh. I hope you get to laugh, wherever you’re going,’ Toby said.

In unison, we said, “Goodbye, Sheela.” With our hands, we shoved dirt to cover her, patted it smooth, and walked back into the house.

Support local storytelling

Available to everyone. Funded by readers.