You Can Gouge Away: Print making provides artistic relief

By Sarah Cook

On March 12th, as part of a two-month exhibit celebrating contemporary native voices, The Dalles Art Center (TDAC) offered a printmaking demonstration hosted by Maggie Middleton, Apprentice Printer at Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts (CSIA).

Maggie Middleton

In the center of the gallery space and surrounded by prints on loan from Crow, Maggie walked participants through the relief printmaking process, giving them the chance to create prints on-site that they could keep.

In an interview conducted by email (published in full below), Maggie highlights the contrast between the specific process featured in the gallery prints on loan versus the process she walked us through—lithographic versus relief, respectively—and names multiple reasons for beginning with the latter, including its low barrier to entry and the fact that relief printing can be done from home.

As a first-time printmaker, I noticed roughly five steps to the process. First and foremost, you choose your image. Maggie helped us along by making samples available, including a beautiful Magpie facing stage right (directions will matter!), which I opted to imitate for the sake of the learning experience.

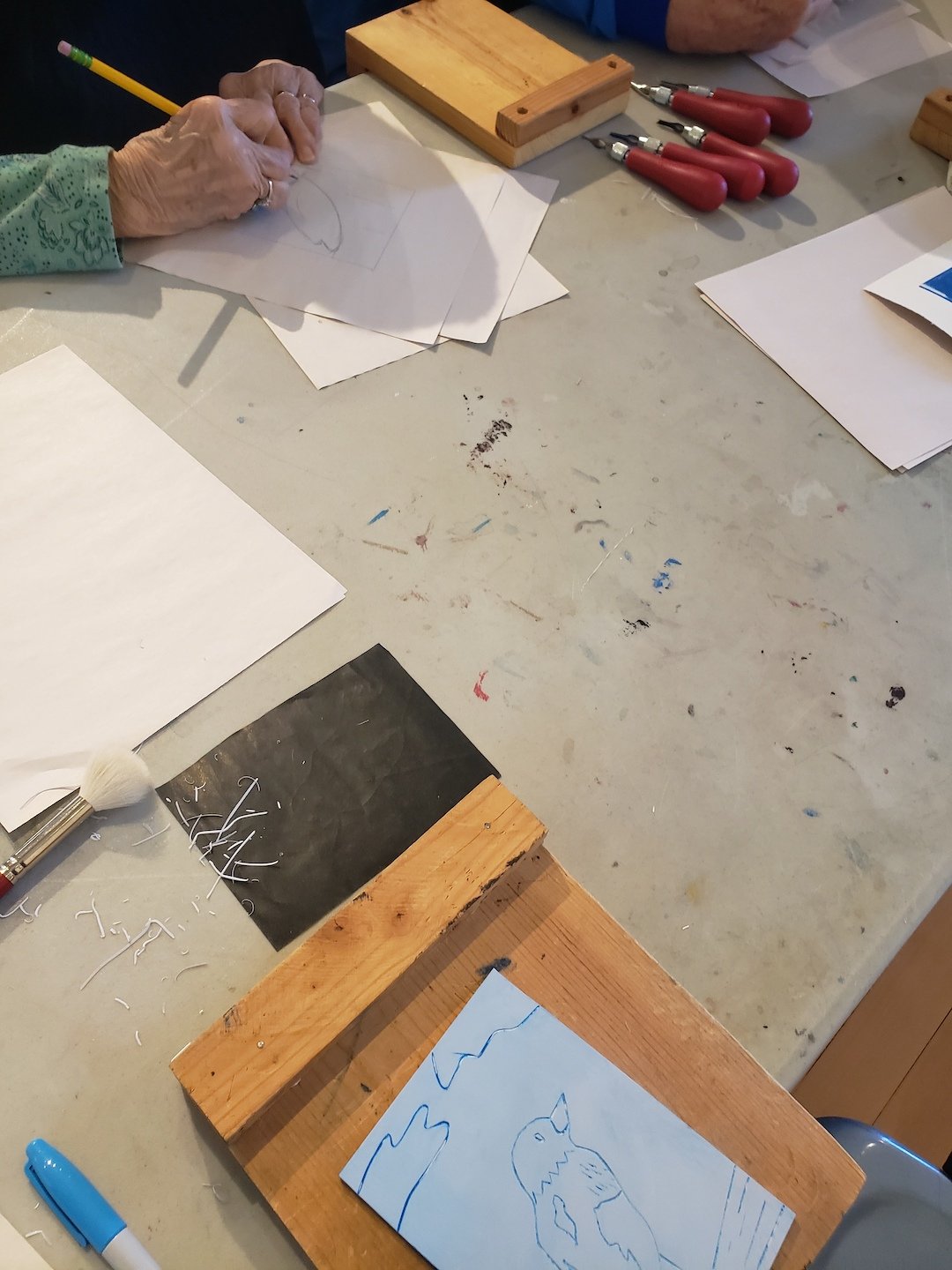

Next, with your image in mind, draw it in pencil on a thin sheet of paper. You’ll then line this up with a piece of carbon paper, directly on top of your printing block, so that you can re-trace it— this time in Sharpie, for ease of tracking where your hand has already gone — which carbon-copies the image onto the block itself.

“Here, my lack of pressure translated into a faint, inconsistently copied image, which I then translated into an invitation to improvise lines where needed.”

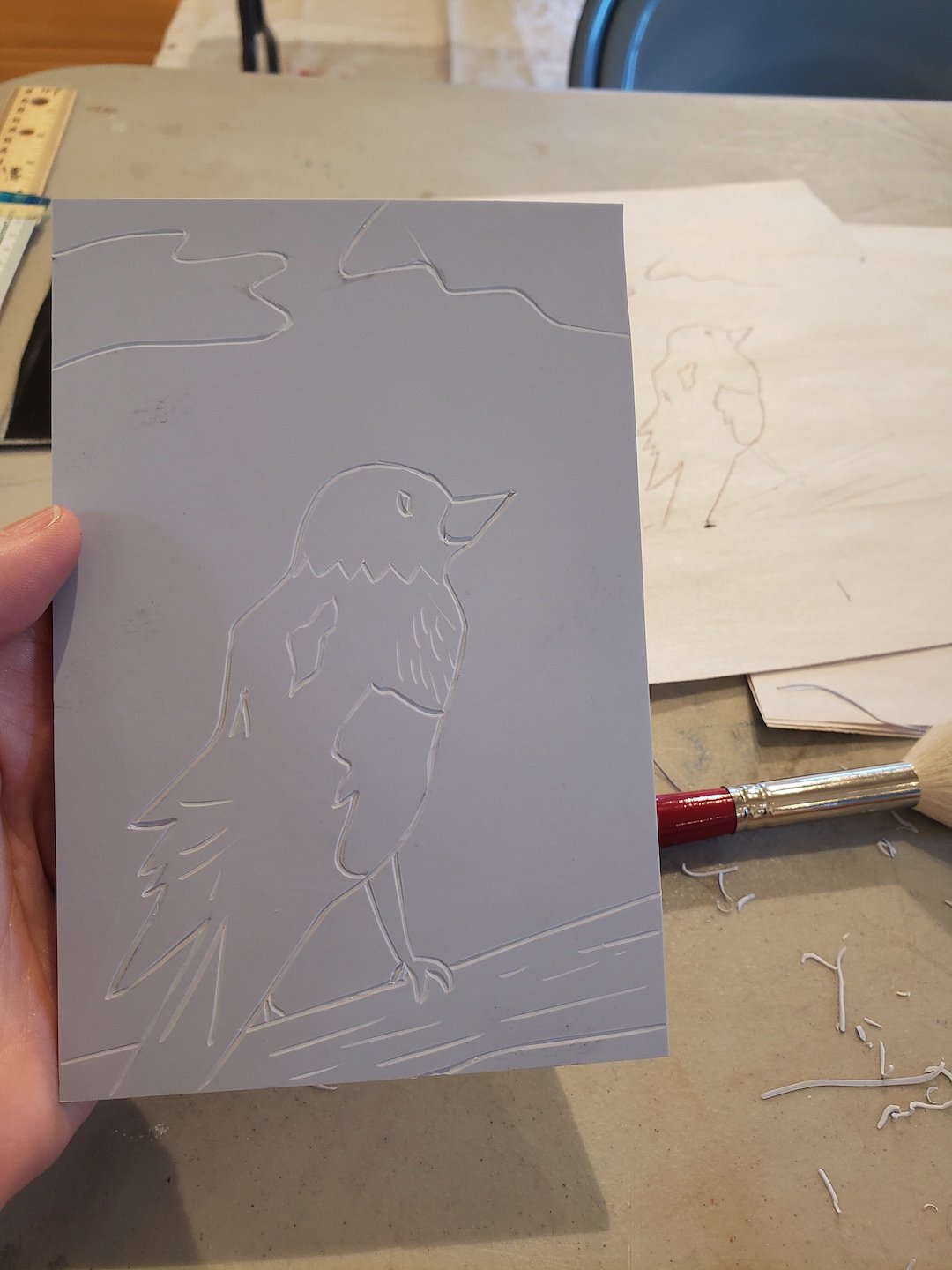

Step four is where the carving begins. Using a tool called a “gouge” and always, Maggie reminded us gently, carving away from your body, you follow the lines of your image on the printing block, creating recesses where the ink won’t stick. This is the first moment in which you might notice the topsy turvy quality of printmaking and, in my view, part of its fun: the carving work itself doesn’t make the image, but rather the blank spaces that make way for where the image will be.

“Note the direction the beak is facing. Now imagine placing this block on a flat, inky surface. Where will the ink stick: on the recessed lines I’ve carved by hand, or everywhere else?”

It’s common for beginners to start with linoleum or rubber printing blocks, which are easier to carve into, though wood can be preferred for its strength while, in my mind, serving as a nod toward the woodblock prints of Edo era Japan. See below.

“The Great Wave off Kanagawa, by Katsushika Hokusai (public domain).”

“These small wooden contraptions rest at the end of the table and create a sturdy, safe edge to push toward as you carve away from your body.”

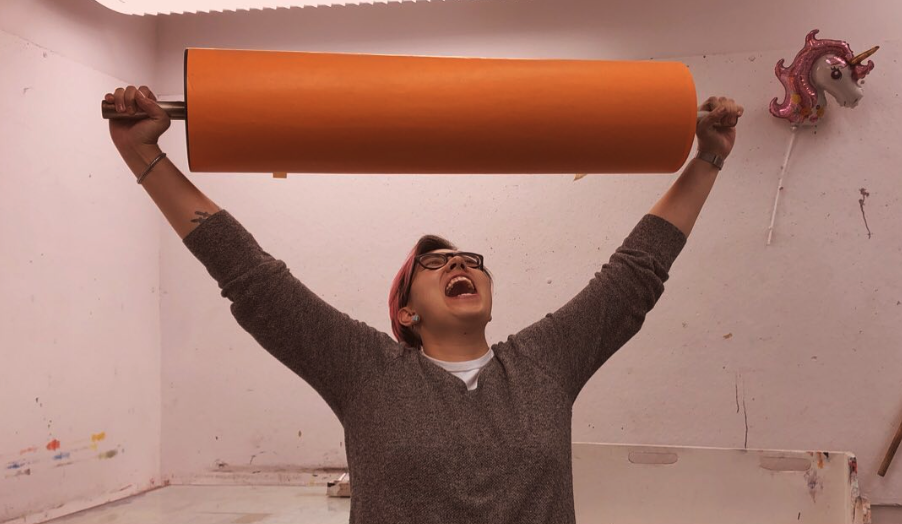

The fifth and final step is the printing itself. Ink is rolled out smoothly on a table with a roller brush so as to evenly pick up the ink, which you then roll onto the carved block itself. This gesture happens not just once or twice, but repeatedly—a key word in relief printmaking seems to be, consistency—making sure that every raised (uncarved) surface is fully coated. The block is then placed, carving side down, onto the final printing paper, where you use all your weight to press, press, press the block everywhere, and evenly (a large wooden spoon, one of Maggie’s tricks, can aid with this process) until you’re confident the ink has transferred fully. How do you know when this has occurred? I asked Maggie at some point along the way, and she spoke not so much about a timeframe or other tangible measurement but an intuitive, bodily sense one develops after years of practice. There can be, of course, desirable effects in a spotty, spontaneous or less consistent printing, which is just one artistic choice that pops up during the process.

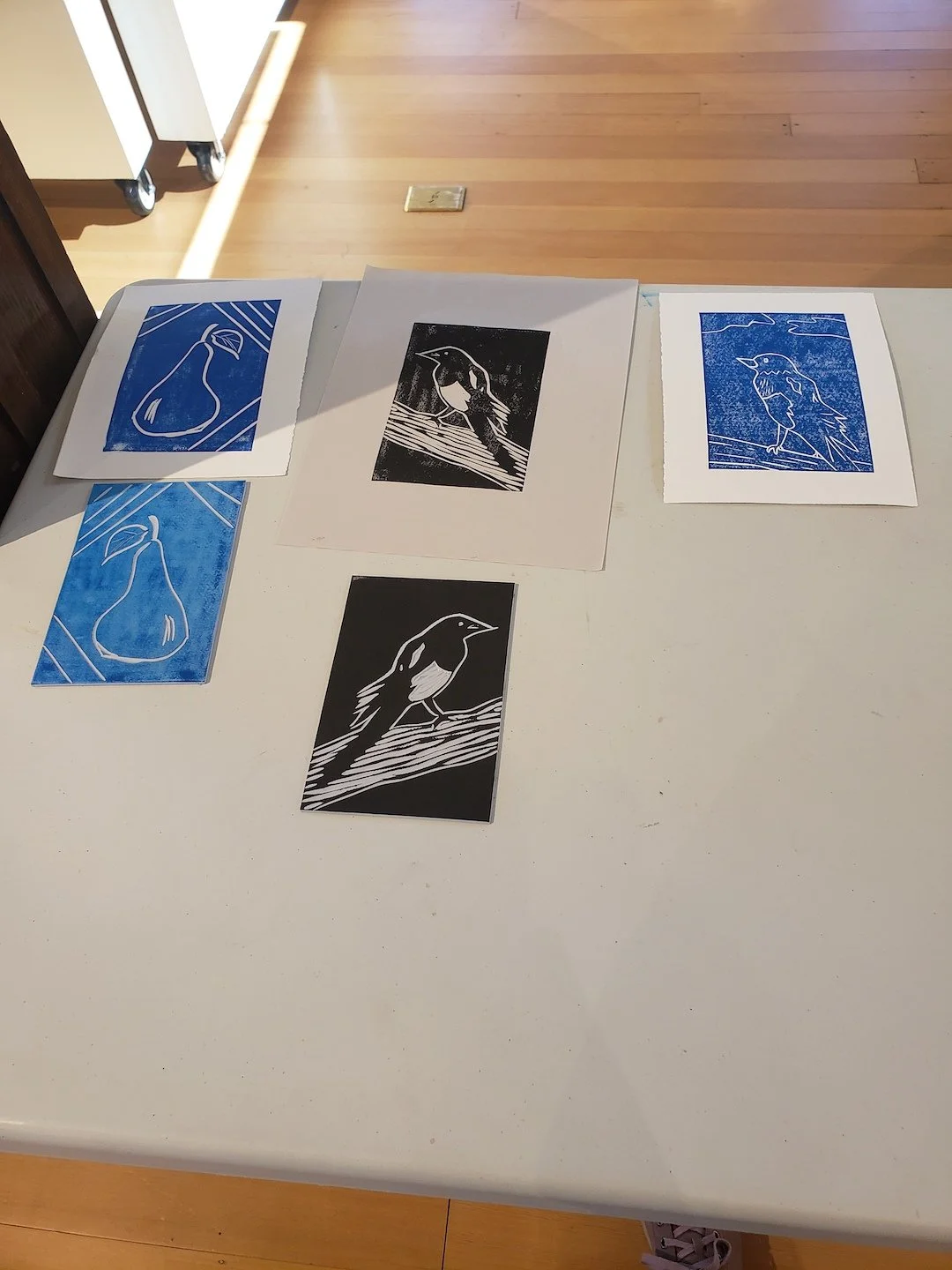

“Some prints lay to dry above two of their corresponding printing blocks. The Magpie in the middle was one of Maggie’s sample images.”

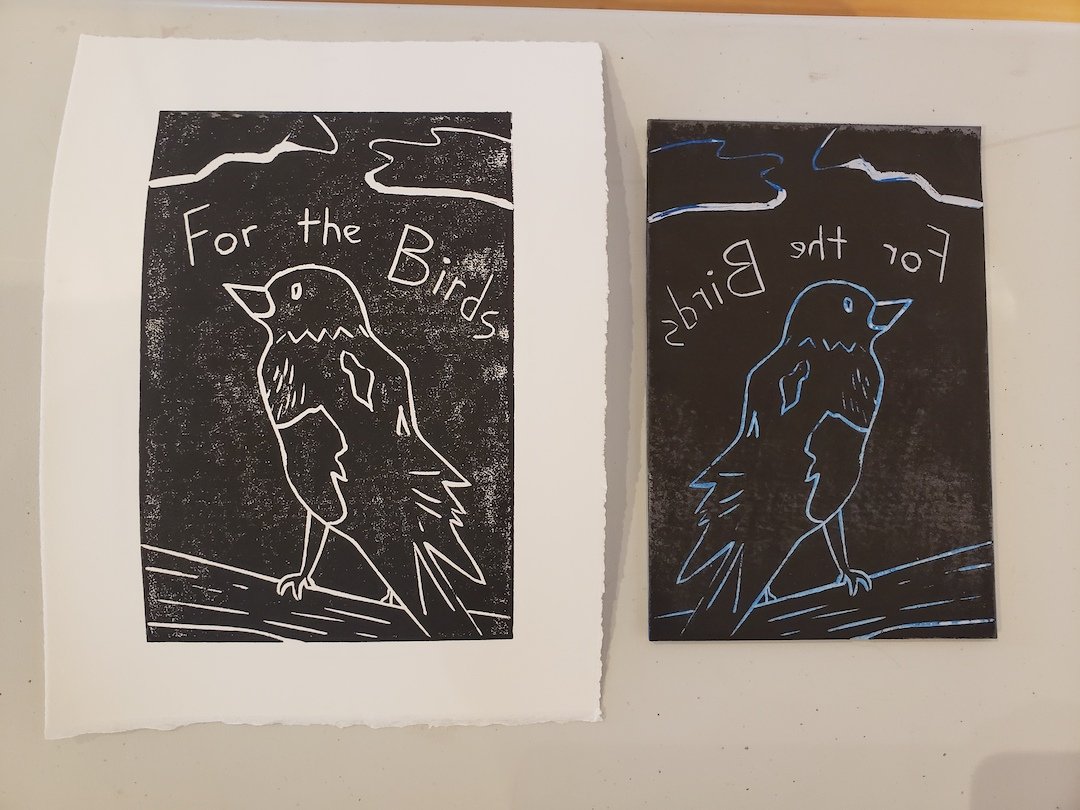

In the end, I printed my image a second time, switching from blue to black ink and insisting on adding words, which must be carved backwards in order to show up correctly on the final product. Full of gentle and effective tricks, Maggie suggested I write my desired words (in this case, the name of my Substack newsletter) in Sharpie on one of the pieces of tracing paper; the thick, bold pen on the thin surface would allow me to turn it over and see the lettering, now backwards, through the sheet, rather than having to picture it all in exact reverse order in my mind’s eye.

“My second and final relief print, on the left, with its printing block on the right. A cloudier, cartoonier version of the sample image, to be sure—perhaps a logo for my newsletter?”

Maggie’s instructions throughout the demo were both extremely friendly and extremely clear—all the learning and experimenting that took place was disguised as a small group of rotating folks just hanging out and playing around with images and inks. The accessibility of her directions, paired with an enthusiasm that didn’t waver whether she’d given an instruction once or ten times, made it easy to immediately love printmaking and to imagine, even a few weeks later, that I’d really like to do it again.

Six Questions with Maggie Middleton (MM)

SC: Can you speak to what drew you to this art form? Did this coincide with you joining Crow, or did one come before the other?

MM: I took my first screen printing class my sophomore year at Oberlin College, and I never looked back after that! I realized in this course that every painting and drawing I had made up to this point would have worked better as a print. I loved the graphic quality of screen print and I found it came naturally to me to create layered images. From this moment on I only became more and more enamored with printmaking, and eventually, I began dabbling with lithography specifically. I was drawn to the range of marks that can only be produced with lithography. After Oberlin, I received my master’s in printmaking at the Eugeniusz Geppert Academy of Art and Design in Wrocław, Poland. While there I made experimental prints on fabric that I then sewed into functional garments. After my two years in Poland, I trained at Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which is a one-of-a-kind technical training program that prepares students to be collaborative printers specifically using lithographic printing. It was through this close-knit alumni network that I was introduced to the current Master Printer at Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts, Judith Baumann. When I found out she was looking for an apprentice printer, I jumped at the opportunity to work in a professional shop that not only publishes prints for amazing artists, but also is an institution that has an important mission statement of making artistic opportunities for Native artists.

SC: I’d love to hear if there are activities you do outside of printmaking (including working in other mediums, but not limited to art-based activities) that inspire or inform the printmaking work itself?

MM: In my free time I enjoy baking, which I think has a surprising overlap with my love of printing, since both activities are time consuming, require planning, and are technically involved. Though I don’t think this informs my printmaking directly, I think that it's a funny coincidence that many lithographers love to bake, and in some ways I think the same problem-solving skill set is employed.

SC: Are there any current projects you're particularly excited about? Are there long-term goals you have for yourself, either within Crow or in the broader art-making world, that you're looking forward to?

MM: I am thrilled to be working with our upcoming group of artists for 2022, being Natalie Ball, Dyani White Hawk Polk, Lisa Jarrett, Fox Spears, and James Lavadour. Each of these artists will stay at Crow’s Shadow for a two week residency, where they will collaborate with the Master Printer, Judith Baumann, and myself to create a print. During this time the artist will draw/create the image for the final print, then they decide on the layering of the print, the ink color, size and composition. Together the print team troubleshoots the technicalities of printing, this is the proofing process. At the end of the two weeks, the artist will sign off on the approved proof that Judith and I will later print as the larger edition of prints. In short, as printers, we make the vision of the artist a reality through print.

SC: How has being the Apprentice Printer at Crow in particular shaped your experience as an artist?

MM: As the apprentice printer at Crow’s Shadow I have been able to see how a variety of artists approach making art; some have an extensive sketchbook practice, while others are research-based, and still others are more intuitive in their mark-making. It has been so educational to watch how a diverse group of artists has created careers for themselves in the arts. Furthermore, printing for other artists allows the medium to be pushed in directions that I would never think of, so not only do I see how various images are constructed, I also get to see new and unique approaches to printmaking.

SC: I’m always curious about gender dynamics in the art world and, in this case, the intersection of gender, cultural representation, and accessibility, which I ask about in light of Crow's mission to create and celebrate opportunities for artistic development for a marginalized population. From your experience, what does that intersection look like in the field of printmaking? I'd love for you to share any insight (whether critical, hopeful, or a mix of both) that you feel called to voice around this topic.

MM: One of the various reasons I was drawn to printmaking was the democratic and communal nature of printmaking. Within a print studio, there is a sense of community since the equipment must be shared and cared for, while also creating art around others creates an air of collaboration while bouncing ideas off of one another (in many ways it was a breath of fresh air after painting alone in a studio for years). Additionally, because prints are made in multiple, there is increased accessibility to one image as the work of art can be disseminated to various people while being at a more affordable price point.

Historically printmaking has been classified more as craft than art, which allowed it to be more accessible to underrepresented groups since craft didn’t have the same gatekeeper tradition as high art. It also has a close history to socio-political revolutions, as printmaking can be a way to spread a visual message quickly. This history has allowed the field to have this radical and accessible quality.

For the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts’ mission statement of publishing prints for Native Artists, collaborating with artists to create editions of prints allows more collectors to have access to one image which increases the representation for the artist. It is an honor to work with an organization that is devoted to highlighting contemporary Native Art.

SC: What were your takeaways from the recent demo at TDAC? Was there anything that surprised you? Anything you especially look forward to when doing these types of community demonstrations?

MM: I had a wonderful time leading the recent in-person relief printing workshop at The Dalles Art Center! It was so exciting to introduce people to the foundational concepts of printmaking that contextualized the exhibition of the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts prints in the TDAC gallery. Though the demonstration was about relief printing and the exhibition featured lithographic prints, I felt that relief printing is an easier introduction that was faster and less equipment intensive, and the most important part to me was that relief printing can be done at home.

Having moved to Pendleton in the middle of the pandemic in May of 2020, this workshop was my first opportunity to work with the larger arts community of the Columbia Gorge; I think that by having this in-person workshop after so many virtual art events, there was a sense of joy among the participants and myself. It is so much fun to see people experiment with the medium and to let their creativity loose! I look forward to doing many more workshops in the future!

--

sarahteresacook.com Read For the Birds, a monthly newsletter