Column: Define your feelings to let them go like a leaf down river

Letting Go

By Nancy Turner

Nancy Turner

To relinquish a view, a feeling, or a desire, requires effort.

One must focus on the present moment, as it is, not on how you’d prefer. Alas, this is easier said than done. Often, we need a ritual: an emotional, spiritual or physical process to facilitate change.

We’re heading into a time of many ceremonies and rituals. These activities have been part of human life from the beginning, and are found in every culture on earth. Ceremonies such as birthday and anniversary celebrations help us acknowledge changes, the passage of time, and to reflect on what the changes mean to us.

We are invited to honor the previous ‘chapter’ of our life and move forward into the next one. They require intention and attention. When our feelings are overwhelmed or empty, a ritual has the power to rejuvenate us. Performed with friends or family, they pull us together and facilitate a sense of love and safety.

There are times when we get caught up in the whirlwind of negative thoughts, fears, and anxieties. Well-meaning people might say, “Let it go.”

If only it were that easy.

We can get caught up in a tizzy of worries and fearful predictions. How do we banish our fears, reduce negative thinking, and move on to a place of calm and inner peace?

One way is by participating in a celebration or ritual that engages us fully. Rituals provide a structure that transforms our emotions when our minds are tired, or in too much pain, to know what to do.

When I was forty, I longed for the open road. I wanted to drive through forests, over mountain passes, and beyond, to the expansive windswept terrain of eastern Oregon. I ached to escape the rubble I had created of my life, to breathe in the tangy smell of juniper and the comforting scent of sage, to hear the call of eagles and howl of coyotes.

It was not possible.

In the madness of midlife and marital discord, my husband found work on a sailing ship. On a sunny day in June, he set off for South America. I was left alone with three young children. Their grief and irritability were a good match for my own; a dry tension sundered us into solitary worlds as we struggled to make sense of our loss. In the late ‘80s, there were no cell phones, no internet, no connection with a loved one far away. My husband, their daddy, was alive somewhere but gone.

I sat in my old rocking chair and reflected on the imminent divorce I both welcomed and feared. My mood oscillated between relief and rage. I grappled with the ominous realities of single parenthood. The children didn’t know what to make of life without their father. He was the one who told them stories every night before bed. I had no idea how to guide their mourning, or my own, for that matter. There was no time or money for counseling. My attempts to soft-pedal the losses hung like tinsel on a discarded Christmas tree.

One day in early July, a few weeks after Peter left, I chanced upon a plan.

The idea rose from my unconscious, I think stemming from a ceremony I’d partaken in when I attended summer camp as a youngster. On the final night before going home, each camper lit a candle, placed it on a little piece of wood, and set it afloat on the gentle Molalla River. We sang camp songs and watched the bobbing lights drift away from shore.

It was magical.

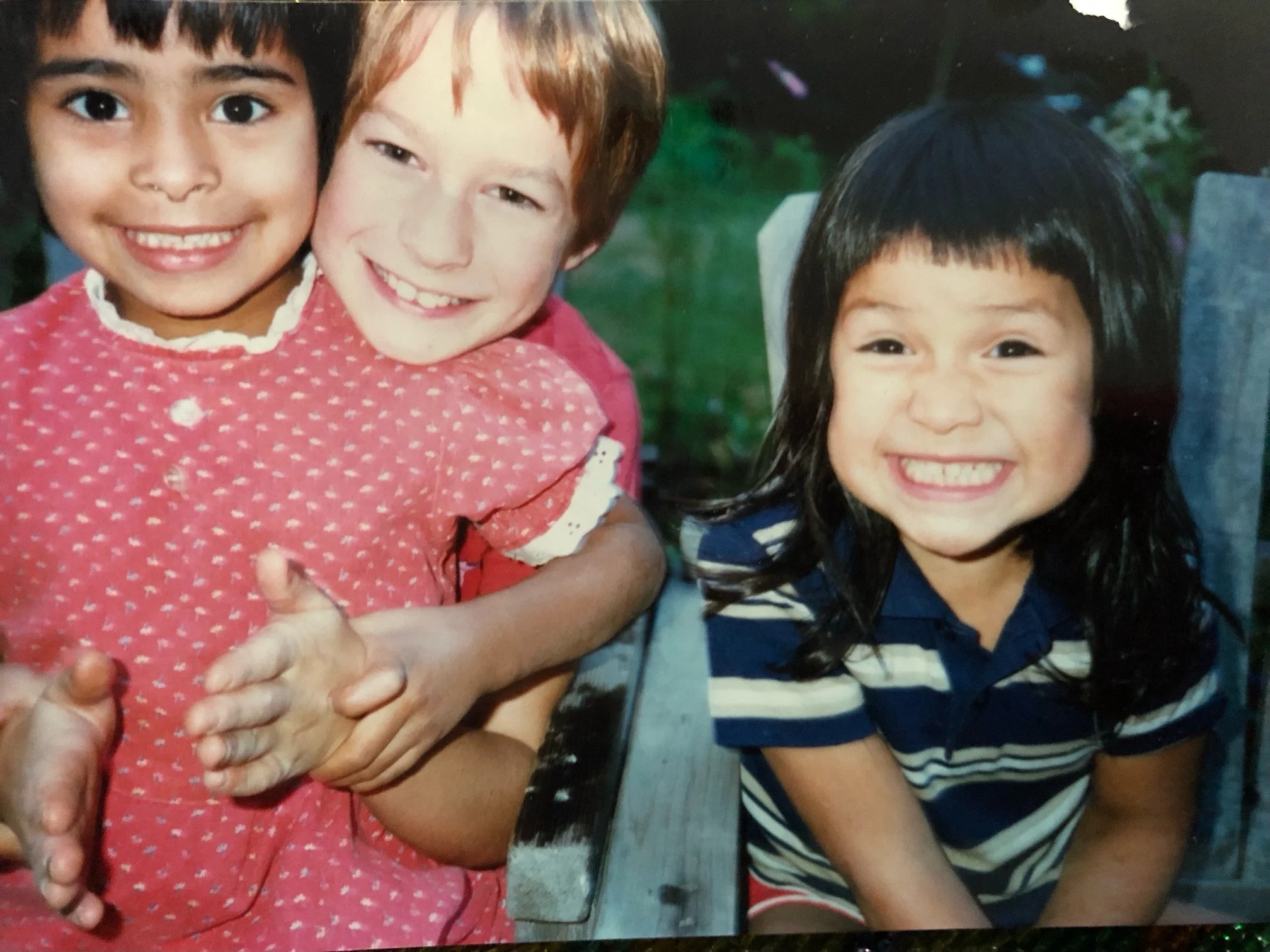

Angela, Elena, Nancy and Toby

I explained to my kids that we would make little wooden platforms that float. We would decorate each one with symbolic objects, add a candle, and take it to the nearby Willamette River. We could say our goodbyes, and let it go.

My energetic ten-year-old, Toby, often wore a red and white soccer shirt that hung to his knees. He had a talent for artistic activities and was old enough to understand metaphors. He was the first to run out to the wood pile to find a suitable raft.

Angela, a petite five-year-old, had only been with our family for six months. She had arrived just before Christmas from an orphanage in Guatemala. Everything our family did was new to her, so she took the idea of building a raft in stride. It seemed weird, but not any more weird than lots of the other things Americans did.

Elena was four. She, too, was adopted from an orphanage in Guatemala but had been with us since she was a one-and-a-half-year-old toddler. Of all the children, she was the most bonded with Peter, and the one least likely to understand why her family had changed so drastically.

The four of us worked for several days on this project. We began at the wood pile, scrounging foot-long slices of split fir. We filled the bathtub with water and tested each plank for seaworthiness, selecting only the ones that floated high enough to keep the flat top dry.

Foot-long slices of split fir buoyed our messages as we let them float away. Putting thoughts into a physical form and releasing them is a way to flip the switch and initiate change within yourself. People write messages on balloons to a loved one who has died or put their thoughts into art and music. Heartfelt thoughts and simple materials were used on the raft above to elicit personal change.

At dinner time we sat around the dining table, eating macaroni and cheese, their favorite. We shared our ideas and firmed up our plans.

“I want to send a message to the universe that says I’m sad,” I said. “I miss the times when Peter and I loved working in the garden together. I’m going to put this packet of carrot seeds on my raft to remind me of those good times. I don’t have the energy to garden like I used to. Now we’ll buy our veggies at the store.”

I did my best to assure them we would have what we needed and prayed I would be able to make it so.

With crayons, we decorated square pieces of paper for sails and secured sticks as masts. We melted wax to hold a stubby candle in place. We dressed each raft with moss from the backyard. I placed little pieces of shattered glass I’d collected along the roadside in a white shell.

“Tears,” I said. “from all of us. More tears than we know.” Toby scattered colorful Legos on the moss in memory of fun times with Dad.

Compared to Angela’s life in a Latin orphanage, our family was the Promised Land. She could eat more scrambled eggs than the rest of us put together. She would have hauled every book in the library home if she’d been allowed. When you’ve gone without, you don’t want to let go. She wanted to cling rather than release. Eventually, she got busy. She grabbed kitchen scissors and headed for the garden.

She cut a yellow summer rose and nestled it on her raft. She explained, “Because it’s pretty and I’m pretty, and I want Daddy to always remember me.”

Elena had no use for metaphors. From under her bed, she brought forth her cigar box of treasures. For hours she pondered which items to put on her raft and which to keep. As far as she was concerned, objects did not carry any particular message or meaning. Her concern was making her raft “bootiful” and in the process, not giving away the gold.

Our creative involvement in this ritual facilitated an opening of our hearts like never before. We talked and laughed, and cried.

Not far from where we lived the Willamette River dawdles through reeds along the shoreline. We needed to position our rafts in the river so the current would carry them away from shore. The only appropriate dock that jutted out far enough was from a private beach. We would be trespassing on private property. The four of us conspired, joined together like outlaws. We would go at dusk, without flashlights, in silence. We wouldn’t take the dog.

The Willamette River falls and rises with the ocean.

For water to be close to the dock, we had to go at high tide. I checked the tide chart. On the night of our “Goodbye ritual,” as we’d come to call it, the weather turned foul. It began to rain, quietly at first. As I reached for my black umbrella the raindrops clattered louder against the windows. I opened the front door and stared out into the night.

“My god, it’s raining cats and dogs! What do you think? Shall we go?” I asked the trio poised silently beside me.

Elena quipped, “I don’t see any cats and dogs.”

With the windshield wipers on high, I drove my old Volvo station wagon to Miles Street, a narrow lane leading to a handful of homes along the waterfront. Hoping to conceal my car, I parked beside a tangle of blackberries. Wearing hooded raincoats and clumsy rubber boots, we all climbed out of the car, clutched bags holding our sacred objects, and assembled in the road. As if on cue, the rain ceased.

“I knew it,” said Toby. “I knew it would stop.”

I whispered, “We need to be quiet, everybody. No talking. Got that, Angela? Toby, you hold her hand. I'll take Elena. Ready? When we get to the end of the dock, we’ll light the candles and put the rafts in the river.”

We made our way past someone’s garage, ducked beneath a living room window, tread across the sandy beach, and stepped up onto the wooden pier.

“Hold onto each other. I don’t want anybody falling in,” I cautioned as I tightened my grip on Elena’s hand. Heaven help me, I thought, if someone sees us.

We clung together, inching our way over wide slippery planks. I could smell the musty water and hear a gull cry as it swooped overhead.

It was impossible to distinguish the dark murky water; there was no horizon. The dark river merged with an infinite black sky.

The match sent out a burst of light and a sweet puff of smoke. I knelt on the dock, leaned over the edge, and set my raft on the water. The yellow circle of light wobbled with the movement of the water. I let go. My throat tightened and I could barely whisper, “Thank you, Peter, for what we had. It’s time to move on. I wish you well.”

Toby lay on his belly and set his off with a slight push. “I miss you, Daddy. Come home.”

Elena’s was next. Toby saw that her arms weren’t long enough. He took her raft and placed it in the water. She chimed, “Have a good life, Daddy.”

Angela shook her head, “No.”

It was hard for her to let go. She cradled her raft for a long time before relinquishing it. After her little beacon of light joined the others on the water’s surface, she gleefully jumped up and down, clapping. As it drifted out to the center of the river, she exclaimed, “I can still see it!”

We watched the tiny twinkling lights float downriver toward the sea, becoming smaller and smaller until only one tiny speck was still visible. Leaning against each other, we basked in a silent reverie, not moving a muscle, until Angela spoke. “I can still see it!”

So it was that our sorrows became sanctified. Certainly, there were hard days following that night, but something had changed. It was an unforgettable turning point in our lives. As adults, my children still recall making those rafts, going out at night, setting them adrift in the river, and letting go.

Support Local News

Available to everyone. Funded by readers.