The Ruins Part 2: Memories Flood Curtiss on Brewery Grade

Steve Curtiss stands next to his International Harvester truck at his home in Hood River.

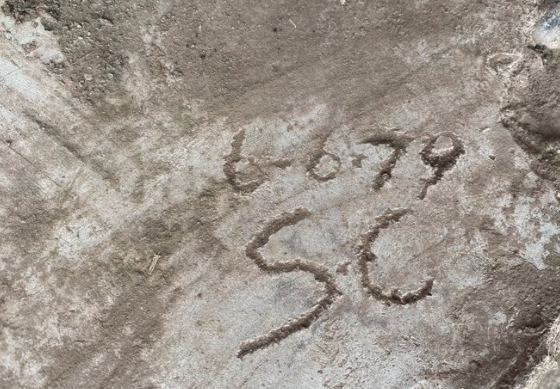

The mystery of SC 6-6-79 is solved thanks to Dianne Epsy. SC stands for Steve Curtiss the last person to legally inhabit the house at the base of Brewery Grade. Here is his story.

By Tom Peterson

Steve Curtiss laid in bed, covered up in an elk skin and could see the stars and the smoke from the chimney through the holes in the walls.

He drifted off to sleep.

When he woke up in the morning, his mustache was froze to his lower lip and snow had drifted across the elk hide.

“But I was warm as toast,” he said.

It was 1978, and Curtiss, just 24, was living in the house at the base of Brewery Grade.

He would be the last to legally inhabit the site.

Curtiss told Columbia Community Connection the following story after Dianne Espy read our story about the ruins and provided his contact information.

Steve, 68, now resides in Hood River with his wife Martha, where he originally grew up.

House at the base of Brewery Grade in its current condition. it sits just a tad east of the bridge that leads to Interstate 84 near the Sunshine Mill. it’s quite a hidden gem, and prone to flash flooding.

Here is a picture of the front of the house when Curtiss lived there some 40 years ago.

Here is an interior shot of the house when Curtiss occupied it.

This boy, Ryan, enjoyed a coconut cream pie at the home in the early 80s, Curtiss said.

Building Years

Back in 1978, the 24-year-old was working in The Dalles. And he met Rosalie Sheerer who owned the house and eventually leased him the property on a trade for rehabbing the old house.

She was in love with the property, which resembled a doll house, with its surrounding plum, peach and apricot trees, he said. She eventually hired an Italian rock mason who added rock gables to the house.

“She scared the shit out of anybody who did business with her,” he said. “She had Coke-bottle lens glasses, a high-pitched strident voice… Curtiss said she kept the City of The Dalles from taking the front section of her property for right-of-way. “She was extremely intelligent.”

Curtiss said Scheerer managed the railroad tie plant and her family had owned property in the Port of The Dalles area.

“No one pulled the wool over her eyes,” he said. “She knew which way the boar dung in the buckwheat.”

Rosalie asked Steve to give her a bid for putting the cottage back in shape. It just so happened that a home trailer plant that was operating at the current site of NORCOR jail in The Port of The Dalles was going out of business. Steve said he could get all his materials, wood, panelling, fixtures, “you name it” at a huge discount.

“I went to her and said I needed $2,800 to do the job,” Curtiss said. “She put on her poker face and wrote me a check.”

It was for $5,000.

“She said, ‘I want you to be able to do everything you need to do,’” Curtiss said. “I loved that woman like a mother.”

Curtiss dug out the rotted wood floors and silt from past floods and replaced them with concrete. He also added supports and interior walls, made updates to the kitchen, living room and bedroom, including windows. He said the house had a cistern which was fed by Dry Hollow Creek that had been converted to additional space in the house. While there he kept a 1940 Chevy ¾ ton pickup, a 1963 Willys pickup and a 1945 Chevy 1 ½ ton.

Nature’s Call

He also fixed up the building to the east of the house and used it for a shop. One night he worked until 11:30 p.m. and shut the doors when an owl swooped down past his head, a feather touching his ear - the first of many times in their relationship.

He was given a puppy in 1982, half coyote. He grew and loved nothing better than chasing wheat trucks. One day he was hit. The dog disappeared, Curtiss said but he later found him lying in his Iris patch, his back injured.

Curtiss took the dog inside and over weeks massaged the dogs back and brought him back to health to where he could walk and run again.

It was a good life, he said, noting he would pick the fruit trees bare to beat the squirrels. He compiled all the pits one time, and put them outside in a two-foot pile. He said the squirrels had them all buried in 45 minutes.

The Flood of ‘83

On Sept. 3, 1983, Curtiss slept in his bedroom against the south wall of the house- nearest Dry Hollow Creek.

He woke to a single drop of water striking him between the eyes. “I woke up to hear the creek roaring,” he said. Curtiss pushed up on the open window above his head and latched it.

“And here come water up on the window like water on a submarine. I picked up my boots and pants. Water started rushing in around the sides of the window. I stepped into the hallway and set my boots down.

“Water was squirting from out of the pipe chase in the stove and was shooting a pencil of water into the sink in the other room.”

Curtiss said a flash flood had occurred up by Mid-Columbia Medical Center and all the water was rushing down Dry Hollow Creek. It overran the banks above the house and inundated it - pouring water through the pipe chase.

“I couldn’t even get my shirt or wallet, and it had $1.500 in it,” he said.

”I went to the police station, but they said, tough. I ended up sleeping on a buddy’s couch.”

“That flood turned my new rugs from beige to chocolate brown.” And the water kept flowing through the home. He moved out. And it took years for him to clean all the silt off his country albums.

Final Notes

Curtiss worked at The Dalles Aluminum Plant until the smelter closed. He retooled and became a physical therapist - 29 years in total including his training.

After the little house flooded, he said it was scavenged for wood, and the roof later fell in. It was also hammered a second time by the flood of 1996.

He said good friend Rosalie Scheerer died in a nursing home in the late 90s.

Thanks to Brown Roofing

This story sponsored by Brown Roofing - see their ads on our website or click here.